By Verena Klemm, Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities (Leipzig)

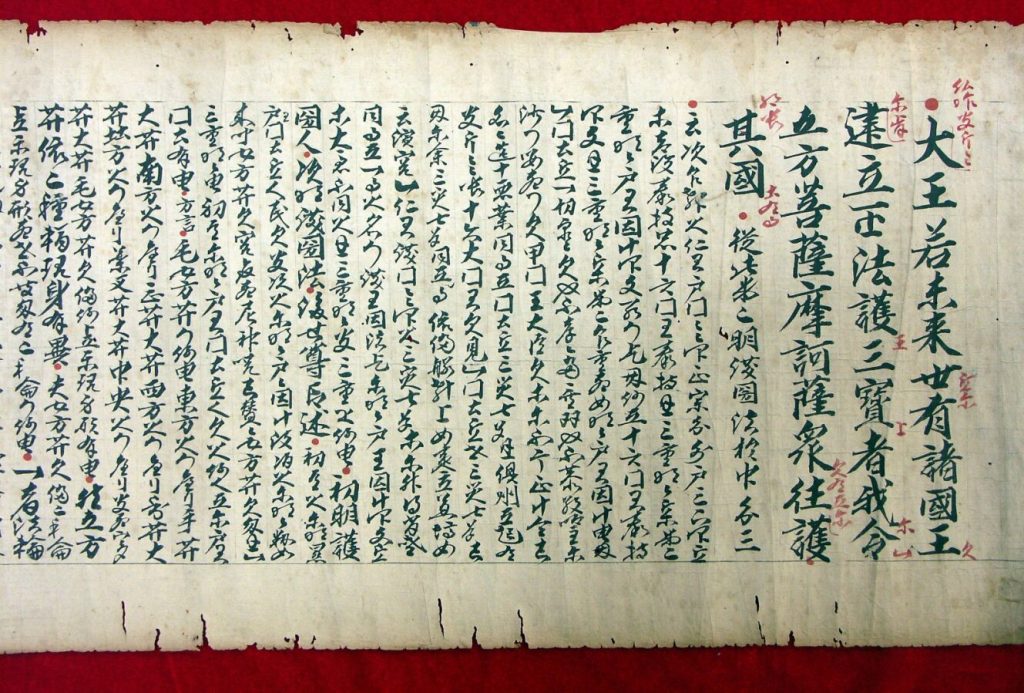

In this blogpost, we browse through a unique personal manuscript belonging to the eminent Ismaʿili scholar Sayyidī Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī (1249–1315 AH / 1833–1898 CE). He was a prominent member of the Daʾudi Ṭayyibī Bohras, an old Ismaʿili Muslim community in Northwest India and other regions around the Indian Ocean, that prospered through maritime trade. The Bohras trace their origin back to the Fatimids, today numbering more than 1 million worldwide.

The manuscript in focus here (Ms. 1662) is part of the Hamdani Collection, a library that migrated with its owner from Yemen to Gujarat in India around in the late 18th century CE. The Collection was transmitted and enlarged through many generations until Prof. Abbas Hamdani (Univ. of Wisconsin, d. 2019), the last heir of the manuscripts, donated it in two stages (2007 and 2014) to the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London (IIS).

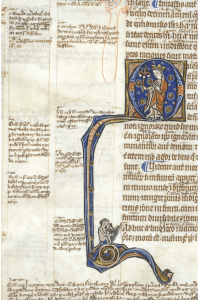

Front cover of Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānīʾs personal notebook [MS. London, Institute of Ismaili Studies, Ms. 1662]

The Ms. 1662 contains 105 numbered folios and measures 19 x 14.5 cm. A British watermark embossed on the paper provides a terminus post quem of 1861 CE. Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī, the owner of the manuscript, apparently used it as a repository for excerpts and extracts from a broad spectrum of disciplines and fields of knowledge. It is brimming with multi-graphic elements such as text snippets, tables, diagrams, sketches, lists, and more. Moreover, he intensively engaged with his notes, as many further notes revolving around his primary notes clearly prove. His marginal commentaries wind like streamers across the pages, in all directions—at the top and at the bottom, in the margins of the page, or even interlinearly.

Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī belonged to a specific environment of scholarly Bohras who experienced a flourishing of their religious culture from the early 19th century until the first quarter of the 20th century under British patronage (according to the colonial “divide and rule” policy that suppressed the majority and protected selected religious minorities). In order to establish and emphasize their identity as the true successors and heirs of the Fatimids (909-1171 CE), the Bohra scholars passionately copied and collected manuscripts of works produced in Fatimid times. Al-Hamdānī´s personal manuscript bears witness to this prosperous and productive period, which he was able to experience and participate in throughout his life.

Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī probably called his personal notebook majmūʿa, his collective or multiple-text manuscript. As this unique manuscript documents, he was interested in many topics. He filled it with excerpts, quotes, and paraphrases from the following disciplines and periods: biblical history as well as historical events in antiquity (Greece, Roman Empire, Iran); Fatimid and Ṭayyibī religious philosophy and doctrine; history; Quran and Hadith; Islamic law; Prophet’s biography; and early Islam. Moreover, we often find him engaging with the fields of mathematics (trigonometry and geometry), chronometry, physics, geography, astronomy and astrology, as well as the secret sciences and magic. For example, we find magical squares and recipes in Gujarati, a regional Indo-Aryan language, evolved from the Sanskrit. In the 19th century, the Bohra scholars opened their native language for Islamic vocabulary in Arabic language and sometimes authored and copied their scientific and religious works in this specific style and in Arabic script.

I have been working with the notebook over the past year and have submitted my findings for publication. My research questions mainly focused on ownership, material, textual practices, and the milieu to which al-Hamdānī belonged. My initial questions, though, were obvious: How do I research such a personal manuscript—one with an overabundance of different texts, numbers, symbols, and forms, created over the course of time, with crumpled as well as blank pages? For its owner, this notebook was certainly more or less well-organized, manageable, and self-evident, but not necessarily for me as a reader and researcher from a completely different time and place. How, then, can I productively use it for my research on Ismaʿili manuscripts, manuscript cultures, and manuscript histories? Furthermore, what does this manuscript tell us about its owner who took on so many roles—namely, collector, compiler, copyist, and commentator? In what follows, I will present some of the insights and ideas I was able to gain during my research.

Private notebooks are not often researched in Arabic Studies since these manuscripts have only rarely been handed down and documented. In contrast, disciplines such as Medieval, Renaissance, and early modern Enlightenment Studies can draw on an abundance of comparable manuscripts like notebooks, miscellanies, scrapbooks, excerpt books, collectanea, and adversaria (there are many names depending on the discipline) that have been produced and kept in literary and scholarly contexts and libraries. Thus, it proved to be very helpful and inspiring to open my research to a broader spectrum of philological disciplines, such as comparative literature and interdisciplinary manuscript studies.

We hardly find any literary or contextual anchor points for research on the role and function of al-Hamdānī’s personal manuscript for his own writings. A few of his epistles (rasāʾil) on religious-political issues, which were topical and important in his community at the time, are stored in private Bohra libraries in India and the IIS. The IIS also houses two copies of al-Hamdānī’s Dīwān, a collection containing poems written during a long stay in Arabia, the Ottoman Empire, and North Africa. His memoirs in Gujarati remain in the possession of his family.

Despite this void of possible biographical or intellectual references, the autographic commentarial activities in this notebook turned out to be substantial sources of knowledge about al-Hamdānī´s scholarly interests and working methods, providing us with answers as to why, with what interest, and how he reflected and commented upon his surely carefully selected primary texts.

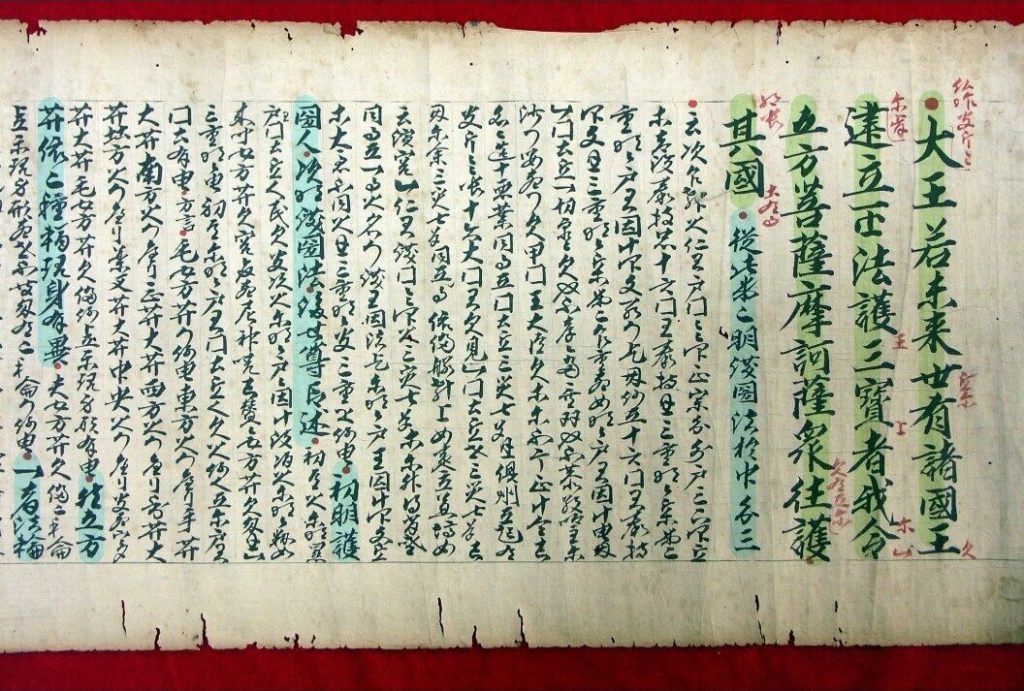

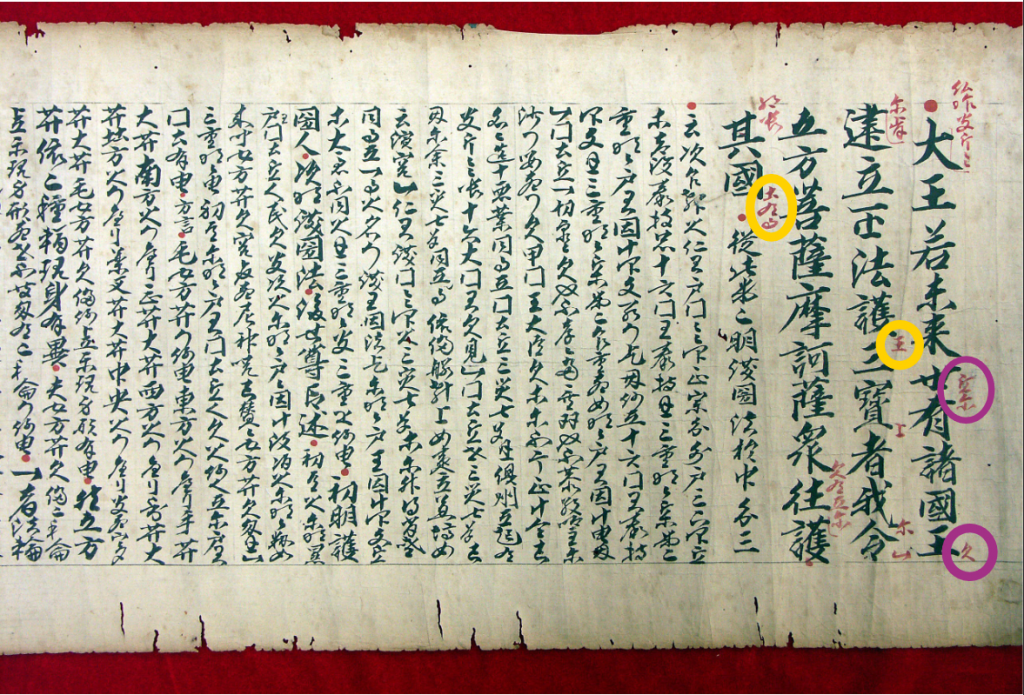

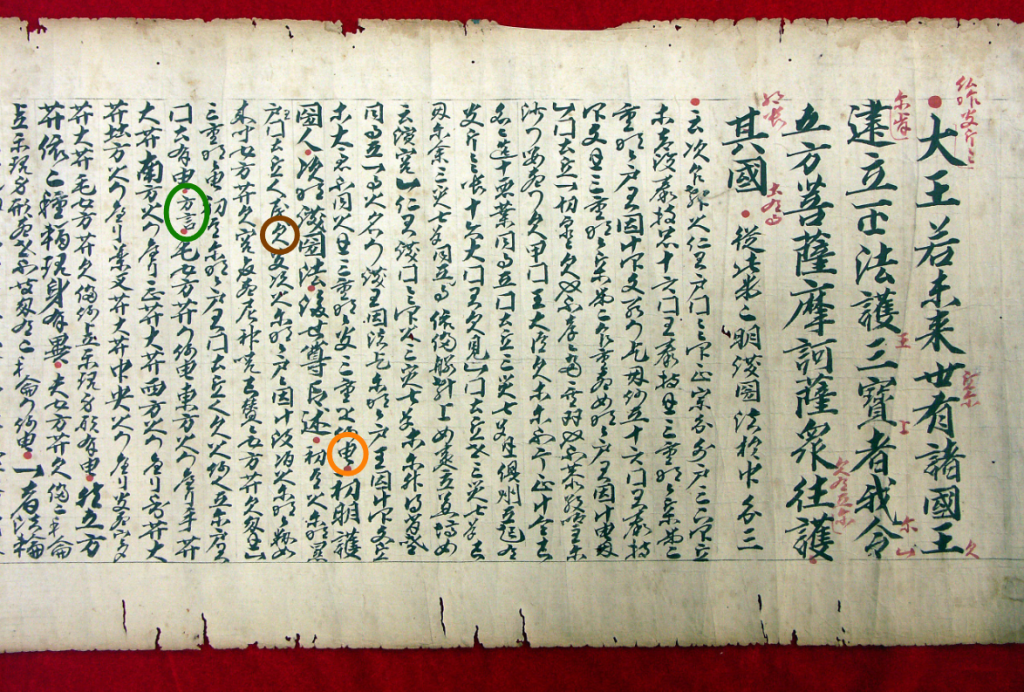

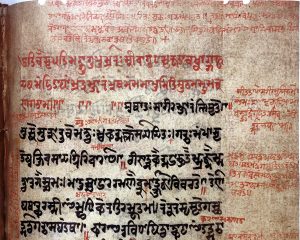

Notes about Notes: First page of a two-page list of the Ismaʿili Imams, with marginal and interlinear commentaries with complementary biographical information (and references to various sources from the Fatimid and Tayyibi literary tradition) [MS. London, Institute of Ismaili Studies, Ms. 1662, fol. 29r]

Indeed, Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī studied many of his copied texts with great interest in their transmission and variance. His readings and comments prove that he approached the written tradition—as manifested in the materiality of the manuscripts—with a decidedly critical and historically-oriented approach. His marginal and interlinear commentaries show that he checked and verified the transmission of a text and studied ownership statements and colophons in the manuscripts he used, often documenting alternative content and variants from other manuscript sources. He even states in some of his commentaries that he discovered interesting manuscripts in other collections, such as in the library of the leader of the congregation (Khizānat kutub al-daʿwa) in Surat. One manuscript he scrutinized was once brought to India from Yemen and contained, as he notes, impressive ownership notes from two prominent religious and political leaders from the 5th century AH (11th century CE) of the close Ismaʿili partner congregation in Yemen.

In this manner, Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī expanded and enriched his primary texts with complementary knowledge from other sources. Additionally, he made the practice of explaining and specifying the diverse content of his primary notes with marginal notes. Some of the short notes in the margins obviously had a merely practical function, intending, for instance, to enable quick orientation in the excerpt by repeating certain keywords of the primary text. Thus, al-Hamdānī´s excerpts, when read together with his commentaries, clearly document his intellectual interests, scholarly engagement, and working methods in the world of manuscripts in which he operated.

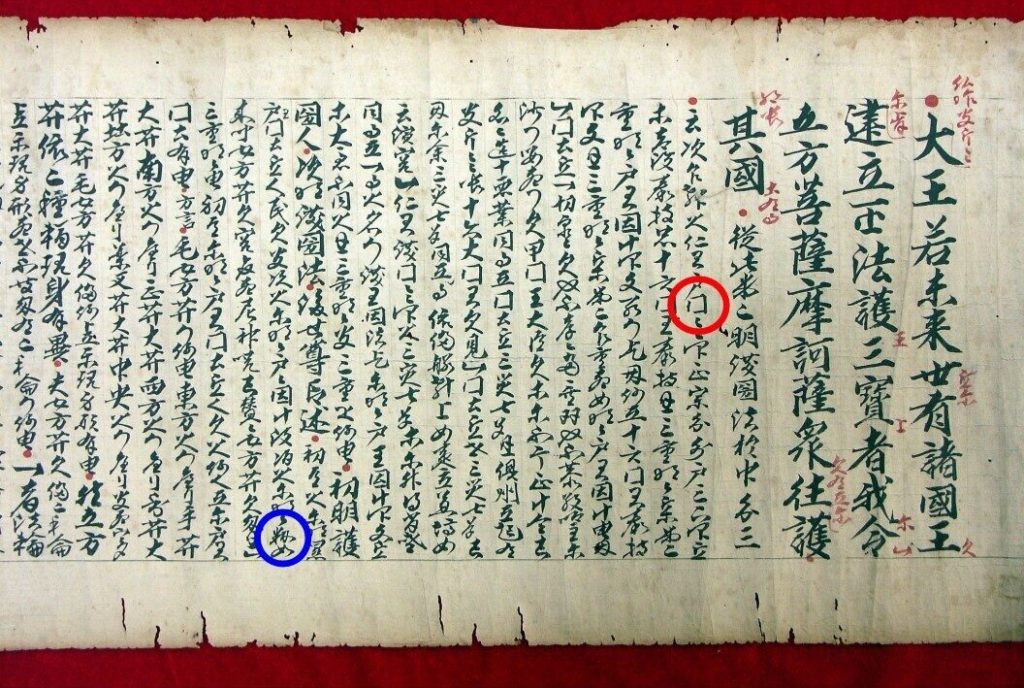

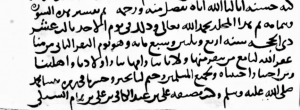

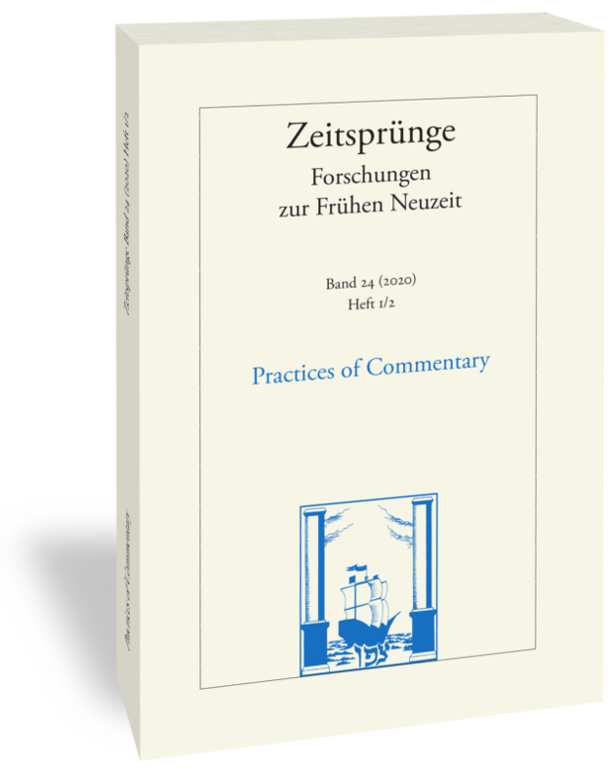

A meaningful constellation—Circular diagram: Conquests and battles in the history of mankind from Adam until the beginning of Islam; excerpt on the right: Animals complain about the cruelty of man (Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ, Risālat al-Ḥayawānāt) [MS. London, Institute of Ismaili Studies, Ms. 1662, fol. 27r]

However, there remains a difficult question: Can we grasp traces of his personal thinking somewhere in his notes and commentarial activities in the manuscript? When I was examining and scrutinizing the manuscript, I came across a possible example. On folio 27 recto, we find a probable constellation or “textual community”—the relationship of two notes in close vicinity. Here, one note might refer to the other; the secondary note may have been generated to express an attitude or an opinion regarding the content of the first note.

How does this possible constellation of the two notes look? The rectangular folio is used here in landscape format. First, filling the center and most of the space of the page, al-Hamdānī has drawn a circular diagram of the pre-Islamic history of wars and conquests as told in the Old Testament and the Gospels, as well as in the historiography of ancient Iran and Arabia, until the life and death of the prophet Muḥammad. This circle is surrounded by another circle in which the chronological distance (in years) between the hijra (the exodus of the prophet Muḥammad from his hometown Makkah, which marks the beginning of the Islamic time calculation) and specific, individual events is noted.

The quotation in the immediate vicinity of this diagram is the possible secondary note, an excerpt from the famous “Epistle of the Animals” (Risālat al-Ḥayawānāt)contained in the rich and syncretistic Islamic proto-encyclopedia “Epistles of the Brethren of Purity” (Rasāʾil Ikhwān al-Safāʾ) from the 4th century AH / 10th CE. As Prof. Abbas Hamdani mentions in his summary of the history of the Hamdani Collection, his great-grandfather Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī must have had a great affinity for the scientific and philosophical concepts and spirit of the group of authors (probably Shiʿi or even Ismaʿili). This empathy for the anonymous Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ (“Brethren of Purity,” as they called themselves) is confirmed and mirrored by a considerable number of excerpts and shorter quotes from the Rasāʾil in the notebook. The epistle in focus here, part of a group of epistles on zoology, is about a court hearing in which animals bring humans to trial before the court of Bīwarāsp the Wise, the king of the jinn. In the excerpt that has been selected by al-Hamdānī, they complain in detail about the cruelty with which humans not only treat each other, but also animals—despite the fact that animals constitute a meaningful and indispensable part of creation. In the excerpt, the spokesman of the predators says that they are not aggressive and cruel by nature but that they learned their behavior from none other than the humans, who have defeated each other in various modes of brutality every single day in history. Here he recalls more than twenty names of kings and conquerors known for war, violence, and bloodshed. All of these personalities took center stage in ancient Iran, Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, Palestine, or Arabia—the same ancient empires whose historical disruptions and breaks are represented in the neighboring circle diagram. There is even an overlap of the two notes regarding the names copied within the circle diagram, with Iskandar and Bukht Naṣṣar (Alexander the Great and Nebuchadnezzar, respectively) appearing in each one.

According to my interpretation, the excerpt at the bottom right-hand part of the folio can be read as a commentary on the content of the circle diagram in its immediate vicinity; of course we never will know this with certainty. But if so, we can assume that Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī mindfully copied his excerpt from the “Epistle of the animals” beside the circle diagram in order to express a personal idea about the major role of violence and martiality in the course of human history.

Thus, as this little portrait of this eminent Bohra scholar and his notebook might show, his dual role as a copyist as well as an annotator can offer glimpses not only into his intellectual interests, but also into his working environment—namely, the specific libraries he once visited and the manuscripts to which he referred. Moreover, we learn something about his working practices and methods. Perhaps a spatial proximity and a meaningful thematic relation between two different notes even reveals a small fragment, or an impression, or an idea, of his thinking and opinion.

Verena Klemm

(vklemm@saw-leipzig.de)

Primary Sources

Epistles of the Brethren of Purity: The case of the Animals versus Man Before the King of the Jinn. An Arabic Critical Edition and English Translation of Epistle 22., ed. and transl. Lenn E. Goodman and Richard McGregor. Foreword by Nader El-Bizri (London: Oxford University Press, in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2009).

al-Hamdānī, Muḥammad ʿAlī b. Fayḍ Allāh: MS 1662: No title (personal notebook). Manuscript Collection of the Institute of Ismaili Studies, London.

Secondary Sources (Selection)

Blair, Ann M., Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2010).

De Blois François, Arabic, Persian and Gujarati Manuscripts: The Hamdani Collection in the Library of the Institute of Ismaili Studies (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011).

Durand-Guédy, David and Jürgen Paul, eds.: Personal Manuscripts: Copying, Drafting, Taking Notes (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2023). (Studies in Manuscript Cultures, 30). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111037196.

El-Bizri, Nadir, ed., Epistles of the Brethren of Purity: The Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ and their Rasāʾil. An Introduction. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2008).

Hamdani, Abbas, “History of the Hamdani Collection of Manuscripts.” In Arabic, Persian and Gujarati Manuscripts: The Hamdani Collection in the Library of the Institute of Ismaili Studies, edited by François de Blois, xxv–xxxiv. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Klemm, Verena: “At the High End of learning – Note taking and Commentary Practices of a Nineteenth Century Ismaili Scholar in India.” In: Marginal Matters: Explorations into Commenting and Glossing Techniques in Arabic Manuscript Cultures, edited by Stefanie Brinkmann. The volume is expected to be published 2025.

–––. “A Library in One Volume – The Notebook of the Ismaʿili Scholar Sayyidī Muḥammad ʿAlī al-Hamdānī from Surat.” Forthcoming in Die Welt des Islams.

Qutbuddin, Tahera. “Bohras.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Devin J. Stewart. Online: Brill, 2013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_25156.

–––. “The Daʾudi Bohra Tayyibis: Ideology, Literature, Learning, and Social Practice.” In A Modern History of the Ismailis. Continuity and Change in a Muslim Community, edited by Farhad Daftary, 331–354. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011 (Ismaili Heritage Series, 13).