by Miguel Ángel Andrés-Toledo and Enrico G. Raffaelli, Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto

Introduction

Zoroastrian communities have provided interpretations of their sacred corpus, the Avesta, since the early phase of their history. The Avesta itself contains commentaries on some of its passages. After the period when Avestan ceased being a living language, and Avestan texts were not composed anymore (around the 4th century BCE), Zoroastrians produced translations and commentaries of their sacred texts to facilitate their understanding.

This blog illustrates the characteristics of the exegetical passages of the Avesta, and of the main corpus of the Pahlavi literature of the pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the most extensive literary corpus of Zoroastrian pre-modern literature.

The Avesta

Some passages of the Avesta are entirely dedicated to commenting on some Old Avestan prayers. These passages have been studied in different specialized works.

Different Avestan passages contain exegeses of words and short commentaries to the contents of the passages themselves. These have received little scholarly attention so far. Some examples of them will be studied here below.

The Wīdēwdād (Law to expel the demons), a ritual text mostly formed by purification rules and laws, is one of the texts containing passages with exegeses of words.

Chapters 8 and 9 of the text, which describe a major ritual of purification of the body called baršnūm, make reference among other things to the washing of the body. Their description switches from references to the washing of the male body to that of the female body. The use in some passages of the pronoun hē, which can mean “him,” “her,” or “it,” makes it sometimes hard to identify whether the text is referring to the body of a man or to that of a woman. To eliminate the unclarity caused by the formulation of the text, the gloss hō. nā (this man) is added sometimes to clarify that the person undergoing purification is a man.

The following examples are found in chapter 8, § 41, and in chapter 9, § 15:

8.41. Av. dātarə. gaēϑanąm. astuuaitinąm. aṣ̌āum. yezica. āpō. vaŋvhīš. barəšnūm. vaγδanəm. pourum. paiti.jasaiti. kuua. aēšąm. aēša. druxš. yā. nasuš. upa.duuąsaiti. āaṯ. mraoṯ. ahurō. mazdå. paitiša. hē. [hō. nā.] aṇtarāṯ. naēmāṯ. bruuaṯ.biiąm. aēšąm. aēša. druxš. yā. nasuš. upa.duuąsaiti.

Maker of the material creatures, Righteous, and if the Good Waters reach first the top of the head, which part does this Lie Nasu hurl itself to? And Ahura Mazdā said: “Then this Lie Nasu hurls itself towards him/her [this man] from the part between his eyebrows.”

9.15. Av. zasta. hē. paoirīm. frasnāδaiiən. āaṯ. yaṯ. hē. zasta. nōiṯ. frasnāta. āaṯ. vīspąm. huuąm. tanūm. aiiaoždāta. kərənaoiti. āaṯ. yaṯ. hē. zasta. frasnāta. āϑritīm. pasca. frasnātaēibiia. zastaēibiia. baršnūm. hē. vaγδanəm. pourum. paiti.hiṇcōiš. āaṯ. hā. druxš. yā. nasuš. paitiša. hē. [hō. nā.] aṇtarāṯ. naēmāṯ. bruuaṯ.biiąm. upa.duuąsaiti.

They must wash his hands first1. And if his hands are not washed, then it makes his whole body unpurified. And when his hands are washed thrice, after his hands have been washed, you must sprinkle the top of his head first. Then this Lie Nasu hurls itself towards him/her [this man] from the part between his eyebrows.

In another passage of the Wīdēwdād, § 23 of chapter 13, a chapter dealing with the dog (an animal who plays an important role in daily and ritual life in Zoroastrianism), a short explanatory gloss follows śiiaoϑnāuuarəz- (actionable, liable (in a process)), a compound belonging in the juridical jargon and therefore less easy to understand than other words:

Av. dātarə. gaēϑanąm. astuuaitinąm. ašāum. yō. spānəm. tarō.piϑβəm. dasti. yim. taurunəm. cuuaṯ. aētaēšąm. śiiaoϑnanąm. āstāraiieiti. āaṯ. mraoṯ. ahurō. mazdå. yaϑa. aētahmi. aŋhuuō. yaṯ. astuuaiṇti. apərənāiiūkəm. dahmō.kərətəm. śiiaoϑnāuuarəzəm. [vərəziiāṯ. śiiaoϑnəm.] paiti. tarō.piϑβəm. daiϑiiāṯ. aϑa. āstriieiti.

Maker of the material creatures, Righteous, whoever gives scarce food to a dog that (is) a young dog, how many of these actions make him a sinner? And Ahura Mazdā said: “as if in this material life he would give scarce food to an underage (child), able to perform competently (a ritual), actionable [he may do an action], so he sins.”

A commentary to a passage is found in the Yašt (hymn) dedicated to the river-deity Arəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā. This Yašt is the fifth of the series of the Avestan hymns. Here, in § 129, the mention of Arəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā’s coat made of beaver fur, is accompanied by a commentary on the beaver:

Av. baβraēna. vastra. vaŋhata. arəduuī. sūra. anāhita. ϑrisatanąm. baβranąm. caturə̄. zīzanatąm. [ẏaṯ. asti. baβriš. sraēšta. ẏaϑa. ẏaṯ. asti. gaōnō.təma. baβriš. bauuaiti. upāpō. ẏaϑa. kərətəm. ϑβarštāi. zrūne. carəma. vaēnaṇtō. brāzəṇta. frə̄na. ərəzatəm. zaranim.]

She is clothed with beaver clothes, Arəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā, (with the fur) of thirty beavers that bear four (young ones) [that is, the most beautiful she-beaver, insofar as it is the hairiest. The she-beaver is an aquatic (animal); when torn at the right time the skin(s) shine to the beholders in full silver (and) gold].

The modalities of interpretation of the Avestan texts through explanations and commentaries are also found in the Pahlavi versions of the Avesta. This points to a continuity in the Zoroastrian exegetical tradition.

Pahlavi exegesis of the Avesta

The Pahlavi versions of most of the surviving Avestan texts have come down to us. They constitute half of the extant Zoroastrian Pahlavi literature. Most of them were composed by Zoroastrian priests between the Sasanian times (3rd–7th century CE) and shortly after the end of the 10th century CE. These versions were composed in Iran. Some reworkings of previous versions, and new versions of Avestan texts, were also made after the 11th century, as late as the 19th century CE. Some of these reworkings and new translations were also composed in Iran, but some of them were composed in India. The vitality until the modern times of the Zoroastrian exegetical tradition reflects the centrality of the Avestan texts in Zoroastrian cult life.

The Pahlavi versions of the Avesta include the translations of the text, and generally also include glosses (portions of text composed of few words) and commentaries (portions of text composed of more than few words) providing interpretations of the Pahlavi translation. These versions are transmitted in manuscripts (mostly having scholarly and teaching use) where the Avestan text alternates with its translation. Usually, each Avestan sentence is followed by its Pahlavi version.

In the translations, the order of the words of the original text is generally reproduced. This often results in sentences whose syntax is different from that of the non-exegetical Pahlavi literature (although the Pahlavi translations cannot be considered senseless reproductions of their Avestan originals). From the morphological point of view, in the translations the marks of the Avestan nominal and verbal inflection, which do not exist in Pahlavi, are supplied by prepositional syntagms and periphrastic verbs.

The glosses are placed right after the Pahlavi words they explain. They comprise, among other things, syntactic complements required by Pahlavi syntax, reformulations of compounds as verbal sentences facilitating their understanding, and synonyms and short paraphrases of words, also facilitating their understanding.

The commentaries are placed after the portions of text they comment on. Their themes are inspired by the contents of the text they accompany. Some commentaries have a high documentary value as they contain quotations from lost Avestan texts.

The Pahlavi version of the Avestan text Sīh-rōzag illustrates some of the main characteristics of the commented versions of the Avestan texts.

The Sīh-rōzag is a ritual text that was composed to be intercalated within other ritual texts, although starting from a certain point it has also been recited as an independent prayer. The text exists in two versions, called respectively “Little Sīh-rōzag” and “Great Sīh-rōzag,” which are transmitted together in the manuscripts. These two versions are both divided into thirty-three paragraphs, each containing short invocations to divine or spiritual beings (generally comprising the names of the entities invoked and one or more qualifying adjectives). The invocations found in the “Little Sīh-rōzag” and “Great Sīh-rōzag” are largely the same in contents, but they differ in formulation: in the “Little Sīh-rōzag” they are mostly in the genitive case, which is governed by xšnūmaine (for the satisfaction (of)) or by other words found in the passages of the ritual texts within which the Sīh-rōzag is recited. In the “Great Sīh-rōzag” the invocations are generally in the accusative governed by yazamaide (we sacrifice to).

The Pahlavi version of the Sīh-rōzag was composed shortly after the end of the 10th century CE at the latest. This translation contains a word by word translation of the formulae of the “Little Sīh-rōzag” and of those of the “Great Sīh-rōzag.” It contains short explanatory glosses to individual words or sequences found in the translation itself. The translations of the paragraphs of the “Little Sīh-rōzag” also contain long commentaries describing the characteristics of the entities there praised. Such commentaries are absent from the Pahlavi version of the “Great Sīh-rōzag”, clearly because they were considered unnecessary, as the treatments on the different beings praised in the text had already been provided in the Pahlavi version of the “Little Sīh-rōzag”

As an example of the characteristics of the Pahlavi version of the Pahlavi Sīh-rōzag we will study the version of § 4 of the “Little Sīh-rōzag.” The paragraph is dedicated to the deity Xšaθra Vairiia.

The Avestan text of the paragraph says:

xšaθrahe vairiiehe aiiōxšustahe marždikāi θrāiiō.driγauue

of Xšaθra Vairiia; of molten metal; of mercy, which protects the poor

Its Pahlavi version says:

Šahrewar [ī mēnōg]; ayōxšust [āsēn-widāxt]; āmurzišn; srāyišn ī driyōšān [kū ǰādag-gōwīh ī driyōšān Šahrewar kunēd; xwadāy ud sālār ud dahibed srāyēnīdār, ud passox-guftār ud šnāsag ī pēš ī Ohrmazd j ādag-gōwīh ī dāmān kunēd; kas-iz kē pad gētīg driyōšān j ādag-gōwīh kunēd, kas ōy andar menišn dahēd. U-š gētīg ayōxšust; čiyōn ayōxšust pad gētīg wuzurg sūd, ōwōn-iz Šahrewar pad mēnōg ud gētīg har 2 wuzurg sūd].

(of) Šahrewar [spiritual being]; (of) metal [molten iron]; (of) mercy; (of) protection of the poor [that is, Šahrewar intercedes for the poor; he is the protector of the lord, the leader, and the ruler, and he is the responder and the knower (of the creatures) who intercedes for the creatures before Ohrmazd; and it is he who gives (= the thought of interceding) in the mind of any person who intercedes in the world for the poor. And his material element is metal; as metal in the material world is of great benefit, in the same way is Šahrewar of great benefit in both worlds, spiritual and material].

In the translation of the paragraph, the theonym Šahrewar translates the form of theonym xšaθrahe vairiiehe (of Xšaθra Vairiia); the nouns ayōxšust (metal) and āmurzišn (mercy) translate the nominal forms aiiōxšustahe (of molten metal) and marždikāi (of mercy); and the sequence srāyišn ī driyōšān (protection of the poor) translates the compound form θrāiiō.driγauue (which protects the poor), which in the Avestan text qualifies marždikāi. The translation of the paragraph is governed, like that of the entire text of the “Little Sīh-rōzag,” by a gloss, pad šnāyēnīdārīh ī (for the propitiation of), which is placed at the beginning of the Pahlavi version of the “Little Sīh-rōzag.”

The gloss ī mēnōg ((who is a) spiritual being) accompanies Šahrewar, identifying Šahrewar as a spiritual being. Further, ayōxšust, a word not commonly used by Pahlavi speakers, is accompanied by the gloss āsēn-widāxt (molten iron), a more commonly used word.

The first part of the commentary, following the paragraph, is focused on Šahrewar’s property of protecting people. This part of the commentary is based on the interpretation of srāyišn ī driyōšān, which in the text identifies an abstract quality, as an attribute of Šahrewar. The second part of the gloss talks about Šahrewar’s connection to metals, which is an important quality of this deity according to Pahlavi literature.

The Sīh-rōzag is one of the texts whose Pahlavi version was revised after its composition. This revision of the text was made in the 16th century, possibly in India. This modified version of the Sīh-rōzag illustrates some of the operations that were performed on the original Pahlavi versions of the Avestan texts when these were revised.

In revising the Pahlavi Sīh-rōzag, some modifications to the original translation of the text were made. Some glosses were eliminated, and others were added. All the commentaries were eliminated, which allowed saving space in the manuscripts.

The revised Pahlavi version of § 4 of the “Little Sīh-rōzag” says:

Xwadāyīh pad kāmag; āsēn-widāxt; āmurzišn; srāyišn ī driyōšān.

(of) Lordship by will; (of) molten iron; (of) mercy; (of) protection of the poor.

Here, xšaθrahe vairiiehe is translated literally as xwadāyīh pad kāmag (lordship by will). Āsēn-widāxt is here the translation of aiiōxšustahe. No other modifications to the translation of the words in the original Pahlavi translation of the “Little Sīh-rōzag” are observed. In addition to the commentary on the text, also the glosses to the text are absent.

After this overview of the characteristics of the Pahlavi versions of the Avesta, as a final note, these versions form the basis of the New Persian, as well as of the Sanskrit versions of the Avestan texts. Both before the modern times and during the modern times, their impact on the Zoroastrian intellectual lore is far from limited to the Zoroastrian exegetical texts. Most remarkably, they are a fundamental source of the contents of the Zoroastrian religious literature in Pahlavi of the Sasanian and early Islamic times, and later, they inspired passages of the New Persian Zoroastrian religious literature.

Notes:

1. The use of “they” and “he/his” alternates to refer to the priests performing the ritual and the person receiving it, respectively. The Avestan text dictates that the priests must wash the hands of the recipient, hence the switch in pronouns.

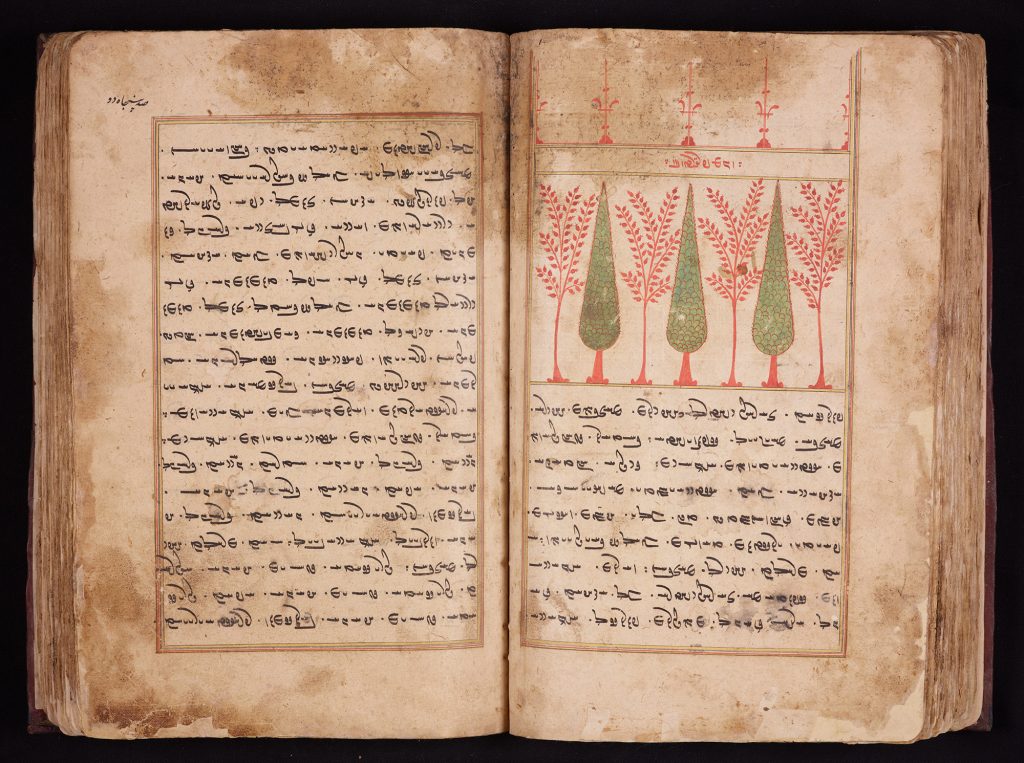

2. British Library. Videvdād sādah, fol. 152r, created in 1647. Source: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=rspa_230_f152r

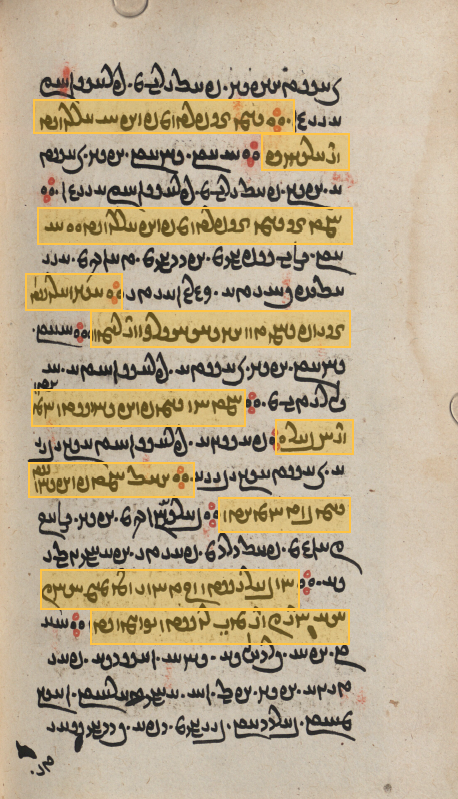

3. München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Awesta-Text Videvdat (Vendidad) mit Pahlavi-Übersetzung – BSB Cod.Zend 48, created in the beginning of the 19th century. Source: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00033729?page=352,353