Commentary was for thousands of years the dominant form of disciplinary and methodological innovation. Yet this key element in global intellectual history has been obscured by the distortions of nineteenth-century philology which prioritized the “original” text and elevated the role of the single author. Accordingly, research on the premodern past has used these values to select which texts to edit, reprint, and incorporate into the broad story of intellectual history — in spite of the clear preeminence of commentary.

We seek to produce a global study of commentary, placing each tradition in its own linguistic and historical context so that we can begin to challenge these distortions. By producing a rich and realistic account of the practices of commentary within various traditions — across languages, cultures, disciplines, and discursive modes — we will collectively produce a truly global account of premodern intellectual history.

Commentaries exercise power over knowledge—and over knowers—and shape wider worldviews by variously authorizing and destabilizing canonical texts, past and present. Writers use commentary to organize and resolve fundamental problems; to assert hierarchy and authority; to challenge that authority; to impose a single interpretive voice; to shout down that voice; to host a multiplicity of voices.

Commentary can be the collective practice of communities of knowledge over many generations, or the notes scrawled in the margin of a private book by an individual. Although commentaries take written form, whether on vellum, paper, or a digital medium, they emerge from oral communities of practice and radiate back into them: in that sense, they have always possessed a multimedial form.

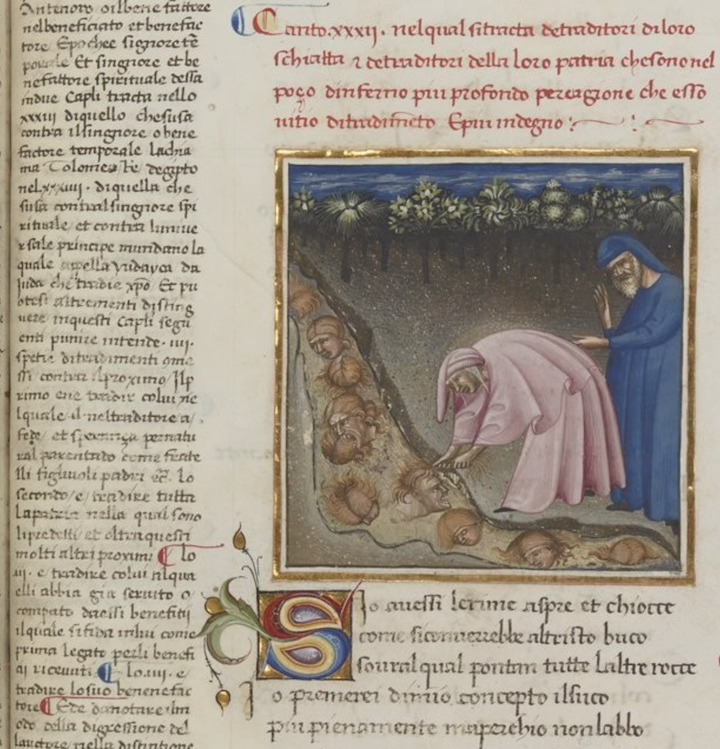

Background image: British Library. Egerton MS 872, fol. 199r. Pentateuch with the Hafṭarot, Five Scrolls, and Rashi’s commentary, 1341.Source: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Egerton_MS_872