by Shuaib ALLY

I am fairly certain I found a copy Ibn Ḥajar had come across of Subkī’s Qur’an commentary. I am excited about this lucky discovery because it is tangible evidence for a network of readership, and also because it establishes Subkī as a known Qur’anic exegete. It is these types of discoveries that are the most gratifying and keep the process of scholarship interesting, so I will tell you all about it.

I was working on an article about the reception of a Qur’an commentary by Zamakhsharī in Mamluk Cairo and Damascus, around the thirteenth to sixteenth century. Zamakhsharī was an early twelfth century Persian scholar who wrote a Qur’an commentary called The Unveiler of the Realities of Revelation and Selected Opinions on Aspects of Interpretation (Arabic: al-Kashshāf ʿan ḥaqāʾiq al-tanzīl wa ʿuyūn al-aqāwīl fī wujūh al-taʾwīl). This book was met with wide acclaim across the Islamic world because it adapted methods of language interpretation from the fields of Arabic linguistics and literary theory to the study of the Qur’an. This allowed a deeper analysis of the language and style of the Qur’an than the commentary tradition had previously engaged in.

The article I was writing was about whether, as has previously been thought, Mamluk era scholars nevertheless held a negative attitude towards Zamakhsharī’s Qur’an commentary because the author held theological (Muʿtazilite) beliefs that did not conform to the dominant (Ashʿarite) theological school in Mamluk Cairo and Damascus. This article, ‘Forbidding the Reading of the Kashshāf,’ was recently published in Asiatische Studien. In short, it turns out that the evidence for this negative positionality is largely exaggerated: the author or the work’s heterodox opinions did not prevent Mamluk scholars from holding the work up as the standard for Qur’an commentary. It was widely used in teaching and research, and it even precipitated a new type of commentary, the supercommentary, because the extra attention this work received meant that commentaries began to be written on it too.

One of the Mamluk era scholars I began working on in connection to this project was Taqī al-Dīn al-Subkī (d. 756/1355). Subkī was a prominent jurist from the fourteenth century and one of the most well-known members of the Subkī family, which produced a number of other notable scholars, including two of Subkī’s sons, Tāj al-Dīn and Bahāʾ al-Dīn. Taqī al-Dīn al-Subkī had a long history of studying, teaching and using Zamakhsharī’s Qur’an commentary in research. Shortly before he died, he had a change of heart. Troubled by some of the content of this work, he swore to never teach it again. This episode was discussed by Walid Saleh previously in an article called ‘The Gloss as Intellectual History: The Ḥāshiyahs on al-Kashshāf’ and precipitated my interest in Subkī.

I began looking into Subkī’s activities related to Qur’an commentary to see if I could determine how he had used the Kashshāf, and to track his use of that work over time. Subkī had written a Qur’an commentary called The Strung Pearl: Explaining the Glorious Qurʾān (Arabic: al-Durr al-naẓīm fī tafsīr al-Qurʾān al-ʿaẓīm). Not much is known about this work; no one appears to have worked on this commentary in secondary scholarship.

Subkī seems to have started writing this work early on in his scholarly career, and probably envisioned it to cover the whole Qur’an in its completed form. For whatever reason, he never got around to finishing it. This could have been due to the many official judicial, administrative, and teaching appointments he ended up holding as he progressed as a scholar. The difficulty in finishing projects because of increasing appointments is probably something the modern scholar of the academy can sympathize with.

Subkī’s Qur’an commentary did not enjoy much of a scholarly reception, possibly because it was never finished. There are also hardly any copies of the work extant, which corroborates this lack of reception. There are only two volumes of the larger work available. One is Ambrosiana 475. C219. It covers in commentary a sizable chunk of the Qur’an, from verse 35 of chapter 19 (al-Kahf, The Cave) to the end chapter 37 (al-Ṣāffāt, In Rows). This volume was copied in 1164/1751, four hundred years after Subkī. Even though the work did not garner much of a reception, at least part of it had remained extant such that it could be copied significantly later.

The second copy is held at the Austrian National Library in Vienna 2052 (Cod. Mixt. 780). This copy is unavailable for physical use because of damage. However, it has been digitized in high quality and is available on the Austrian National Library site.

This is a two-volume copy; it covers, in this order, from the beginning of chapter 48 (al-Fatḥ, The Victory) to verse seven of chapter 59 (al-Ḥashr, The Mobilization). It then covers the first seven verses of chapter 14 (Ibrāhīm, Abraham).

When writing a commentary, scholars did not necessarily start writing them from the beginning of the work they were commenting upon, such as the Qur’an; they often started at some other point, and later may have filled in the other sections to make a complete work. They may then have gone back and revised the previously written sections to polish the work as a whole. Other times, their commentary might simply remain on portions of the Qur’an, either because they only intended to write on that portion, or because they never got around to finishing the project. This practice was facilitated by the nature of the chapters of the Qur’an, which are discrete units and not necessarily chapters in an order.

This volume of Subkī’s Qur’an commentary is an example of this writing process, where the material written does not correspond to the order of the codified Qur’an: he wrote a commentary on eleven or so chapters towards the end of the Qur’an, in order, and did not finish commenting upon the final chapter (chapter 59) in that series, which has 24 verses. Instead of finishing that chapter, he then went back to start writing on a solitary chapter (chapter 14) much earlier in the Qur’an, which he also did not complete. This overall process of writing and/or compilation, incidentally, is not much different from the writing of a monograph or other large project today.

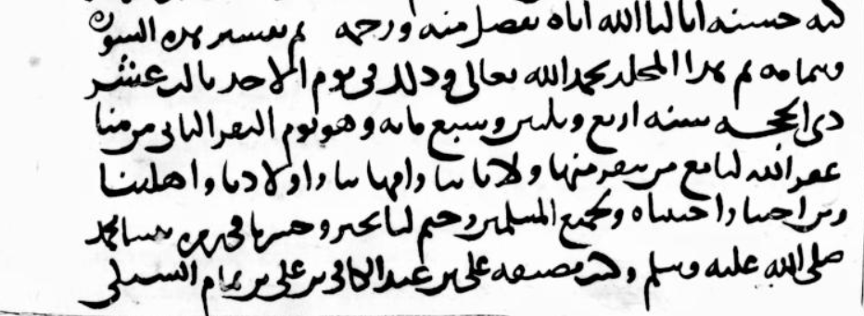

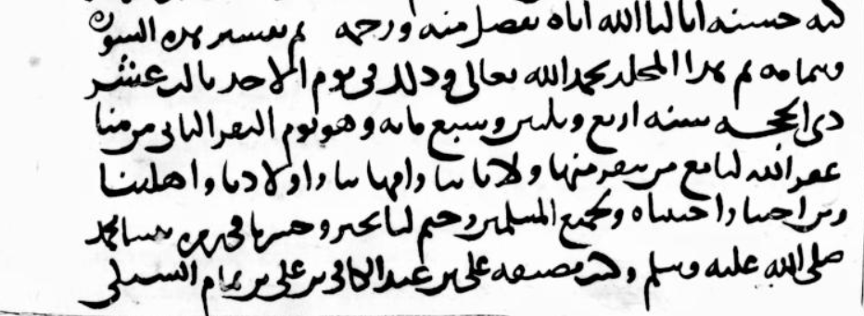

These judgements about authorial process can be made because the Vienna copy was written by Subkī himself (it is an autograph), which is exciting! Here is a note in his hand that he wrote to sign off a section (a colophon) of this copy:

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 2052 (Cod. Mixt. 780),

folio 192a. Courtesy: Austrian National Library.

In Arabic, this reads:

تم تفسير هذه السورة، وبتمامه تم هذا المجلد بحمد الله تعالى، وذلك في يوم الأحد ثالث عشر ذي الحجة سنة أربع وثلاثين وسبعمائة وهو يوم النفر الثاني من منى. غفر الله لنا مع من نفر منها، ولآبائنا وأمهاتنا وأولادنا وأهلينا ومن أحبنا وأحببناه ولجميع المسلمين، وختم لنا بخير وحشرنا في زمرة نبينا محمد صلى الله عليه وسلم. وكتب مصنفه علي بن عبد الكافي بن علي بن تمام السبكي.

In English:

End of the commentary of this chapter, and with its end, thus ends this volume, with the praise of God the Most High. This is on Sunday, the thirteenth of Dhū-l-Ḥijjah, year seven hundred and thirty four, the day of the second departure from Minā. May God forgive us along with those who departed from there, and our fathers, our mothers, our children, our families, those who love us and those we love, and all Muslims; and grant us a good end, and resurrect us in the group of our Prophet Muhammad – God send peace and blessings upon him! Written by its author, ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-Kāfī b. ʿAlī b. Tamām al-Subkī.

The ‘day of the second departure from Minā’ Subkī mentions in this note is a reference to one of the pilgrimage rites. Pilgrims stay overnight in the Minā valley and leave there to Makka either on the twelfth or the thirteenth of Dhū-l-Ḥijjah, in the hijri calendar. Subkī’s reference to this date and his prayer for those departing is a possible indication that he was among them. The date from this note is 734 AH (1334 CE). Subkī would become chief judge of Damascus a few years later, in 739 AH (1339 CE), and would subsequently take up a number of prestigious teaching positions there as well. It is possible that this was one of the reasons his work on the commentary stalled.

In any case, while a closer look at what is extant of Subkī’s Qur’an commentary in these two copies is deserved, it was clear to me even from a cursory look that Zamakhsharī was one of the primary interlocutors of Subkī’s work in this period of his life and scholarship.

Because of my interest in Subkī, I also began looking into biographical notices about him recorded in medieval biographical dictionaries and chronicles. One of these biographical dictionaries was written by Ibn Ḥajar (d. 852/1449), a fifteenth century scholar and judge. He remains one of the most immediately recognizable scholars in Islamic history because of a commentary he wrote on a collection of highly authenticated reports of Prophetic sayings and activities, which he called Inspiration of the Creator (Fatḥ al-bārī). This commentary continues to be consulted today for interpreting Prophetic reports. Ibn Ḥajar’s biographical dictionary was about people who had passed away in the eighth century hijri, corresponding to about the fourteenth century of the Gregorian calendar. He named this work Concealed Pearls: Notables of the Eighth Century (Arabic: al-Durar al-kāmina fī aʿyān al-miʾa al-thāmina).

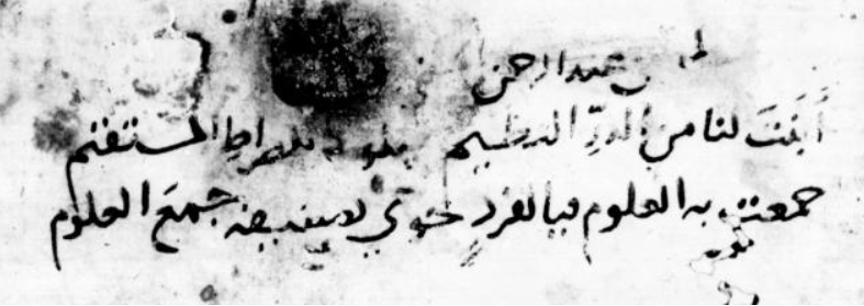

In this work, Ibn Ḥajar wrote that he had seen a volume of Subkī’s commentary. He had seen on the cover of that volume a couplet of poetic verse written in the hand of another prominent scholar, Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Ibn al-Ṣāʾigh al-Ḥanafī (d. 776/1375). Scholars of this period would write verses of poetry, or whole poems, for various social purposes. One such reason was in praise of the work a contemporary scholar had written. Ibn al-Ṣāʾigh appears to have written verses of this nature on this copy of the commentary Ibn Ḥajar had seen. They serve a function similar to the endorsements from academic celebrities found on modern print books: to sing the praises of the work.

The couplet Ibn al-Ṣāʾigh had written was:

أتيت لنا من الدر النظيم سلوكا للصراط المستقيم

جمعت به العلوم فيا لفرد حوى تصنيفه جمع العلوم

You laid out for us, through pearls strung, the way to the straight path

You combined in it all the fields – acclaimed is one whose writing encompasses all!

Amazingly, this couplet is on the cover of the Vienna copy! Here it is in all its glory:

The legible part of the first line in the figure above appears to read, “By Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ḥanafī;” that is, Ibn al-Ṣāʾigh. This introduces the couplet in the two lines just below it.

I am fairly certain that the copy of Subkī’s Qur’an commentary Ibn Ḥajar said that he had seen, with a couplet in praise of it in the hand of Ibn al-Ṣāʾigh, is in fact the autograph copy now held at the Austrian Library. What sheer luck that Ibn Ḥajar had pointed out these verses in his biography of Subkī, and they turn out to be in the hand of Ibn al-Ṣāʾigh preserved in this copy in Vienna!

Working with commentary and manuscripts can sometimes yield these connections and serendipitous finds. This discovery was a side note in the article I had written about the reception of the Kashshāf; it was not substantively related to that topic. However, it was still one of the more exciting moments for me in the research for that paper. Of course, scholars owned books, and autographs or scholar-owned copies were often preserved because of their value. Nevertheless, whenever I find specific instances of copies of pre-modern works with evidence that they were owned by significant medieval scholars, the connections between scholars and disciplines, authors and readers, and the transmission and preservation of knowledge past and present is all brought into greater relief.

*This blog post draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.