by Anthony FREDETTE and Simon WHEDBEE

Many surviving twelfth-century Latin commentaries associated with the influential cathedral schools of northern France have in common the focus, treatment, and scope of the ars grammatica: the philological exegesis of texts for grammatical, logical, and rhetorical instruction. One medieval commentary on the Georgics of Virgil demonstrates the wide application of philological exegesis in medieval scholastic thought, branching out from studies of the poem’s language along the lines of the Trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) into the natural sciences. An Aeneid commentary appearing to have the same provenance as this Georgics commentary recalls the teaching of Anselm of Laon (1050-1117). Modern scholars attribute its authorship to a slightly later figure who may have learned from Anselm or his disciples: Hilary of Orleans (first half of the twelfth century). Based on numerous similarities between the commentaries, we may tentatively attribute the Georgics commentary to Hilary as well, though only future studies can confirm this.

Hilary’s twelfth-century study of the Georgics forms part of a larger body of medieval scholarship on Latin poetry. Specifically, this commentary on the Georgics, which circulates in three surviving manuscripts, accompanies several other texts associated with Hilary or his school: one on Virgil’s Aeneid (previously mentioned), one on Virgil’s Eclogues,one on Statius’ Thebaid, and one on Lucan’s Pharsalia. We are currently working together with Alexander Andrée — professor of Latin and Palaeography at St Michael’s College at the University of Toronto — to collate the three manuscripts with hopes of eventually preparing an edition and full-length study of this intriguing medieval commentary on such an enduring work of classical Latin poetry.

Figure 1. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, lat. 34. This folio contains the beginning of the Georgics commentary.

Our initial transcription of one of the three manuscripts, Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, lat. 34 , has yielded some promising first fruits. Among the most obvious and perhaps predictable features of Hilary’s commentary is the large extent to which it is composed of paraphrases and reworkings from surviving antique and early medieval glosses on the Georgics. Principal among these are the writings of the fifth-century grammarian Maurus Servius Honoratus and two collections of medieval scholia: the Commenta Bernensia, preserved in a single tenth-century manuscript, and the Brevis expositio, an incomplete commentary that survives in four manuscripts from the ninth to eleventh centuries.

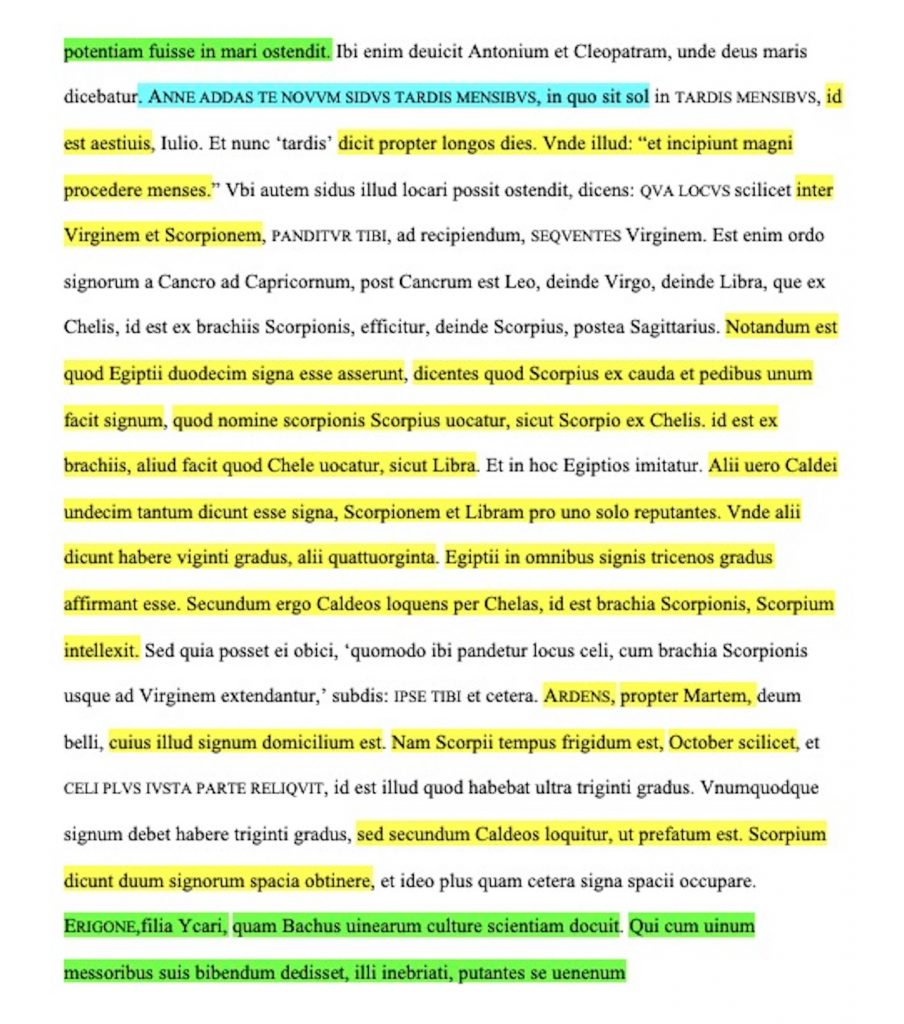

Figure 2. Our working transcription of the Georgics commentary. Lemmata from the poem are in small caps. Text taken from Servius is in yellow, that from the Bernensia in green, and that from the Brevis expositio in blue to highlight the composition’s interwoven nature.

Among these three sources that Hilary utilizes, Servius predominates, given the antiquity of his commentary and his own high reputation throughout the Latin Middle Ages as a classical grammarian par excellence. Figure 2 highlights the manner in which Hilary weaves together glosses from the three older sources to great effect: the text of Servius is in yellow, the text of the Bernensia is in green, and the text of the Brevis expositio is in blue.

Hilary not only copies and paraphrases teachings from these sources, but also cites them directly. For example, while discussing the poet Virgil’s characterization of crops as ‘happy’ (laetas segetes), Hilary references Servius’ substitution of the adjective ‘happy’ with ‘enriched’ (pingues), which he even slightly critiques:

Tribus modis impinguatur terra: intermissione arandi, combustione, stercoratione. Cineratione quoque dicit Servius, sed sub combustione continetur.

[The earth is enriched in three ways: by leaving it fallow, through controlled burns, or through manure. Servius also says that ash can be used, but this falls under the category of controlled burns.]

Other stock phrases that deliberately introduce a Servian interpretation are ‘Servius dicit quod,’ ‘vel aliter secundum Servium,’ and ‘testante Servio’ (‘Servius says that,’ ‘or, put another way according to Servius,’ ‘as Servius testifies’). More often than not, Hilary does not cite an authority or even signal that an authority has been consulted, but merely slips the paraphrased material into his own stream of interpretation.

Because Servius’ commentary on the Georgics is thorough and holistic in its interests, Hilary employs its insights in a wide variety of ways that neatly correspond to the techniques and interests that he himself employs in his more ‘original’ acts of interpretation. This fact, coupled with the widely recognized authority of Servius, suggests that Hilary and his disciples may have consciously styled their hermeneutics and pedagogy (if indeed this manuscript does witness to a teaching tradition) on that of Servius. Any future edition of Hilary’s commentary will have to clarify its complex relationship to the Servian glosses.

It is not only to the ancient past, however, that Hilary turns his gaze. The commentary also reveals an intense and intricate familiarity with earlier and contemporary medieval texts that belong to a startling variety of genres and topics that fall outside the purview of modern Classics departments. Some significant later texts from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries also seem to echo teachings otherwise only attested in Hilary’s Georgics commentary, suggesting that it enjoyed some popularity and influence after its initial dissemination.

Authors that Hilary’s commentary either directly cites, paraphrases, or seemingly inspires include: Probus, Macrobius, Varro, Priscian, Aelius Donatus, Ambrose of Milan, Bede, Isidore of Seville, Sedulius Scotus, John Scotus Eriugena,Remigius of Auxerre, Heiric of Auxerre, William of Conches, Thierry of Chartres, Hugh Folieto, Peter Helias, Jean Buridan, Matthew Paris, John of Garland, Alexander Neckam, Roger Bacon, Albert The Great, Alexander de Villa Dei, Eberhard of Béthune, Huguccio de Pisa, and Thomas Aquinas.

Regardless of whether Hilary’s Georgics commentary directly engaged with or influenced these authors or whether they are all drawing from a common corpus of sources, it is clear that the teachings in Berlin 34 draw us deep into the scholarly and educational environment of twelfth- and thirteenth-century France. Hilary’s teachings exemplify a truly interdisciplinary approach to reading classical literature, as texts that share readings with Berlin 34 fall into categories as diverse as grammatical theory, biblical exegesis, historical works, didactic poetry, encyclopedias, and the natural sciences.

The content of Hilary’s commentary reminds modern historians of both the flexibility that medieval scholars enjoyed in navigating their studies of the liberal arts and their deep commitment to the guiding methods of the ars grammatica(‘philology’). Hilary principally endeavours to understand the intended meaning of the poem by subjecting each word to grammatical parsing, comparison with other poems, and contextualization through supplementation of information from other areas of ‘liberal’ expertise. At the most basic level, Hilary accomplishes his goal of elucidating the ‘meaning’ of the Georgics — an at times difficult poem replete with precise agricultural language — by turning to the technical terms of medieval formal grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

Hilary’s observations on the grammar of the poem range from simple explanations to more theoretical observations. For example, Hilary will note the noun case or verb conjugation of various passages in the poem (1), point out syntactical features (2), and explain specific uses of words or phrases that might have seemed archaic to his audience (3), as in the following three examples:

(Note: lemmata that refer to the text of the Georgics are noted in small caps, while the commentator’s thoughts are rendered in simple italics)

| 1. Vel habite id est habentes. Preteritum passiui pro presenti actiui. |

| [Or ‘HAVING BEEN HAD, ’ that is to say ‘having.’ Virgil uses the passive past participle in place of a present active participle.] |

| 2. Relictis nidis, ablatiui absoluti. |

| [‘WHEN THE NESTS ARE ABANDONED,’ an ablative absolute clause.] |

| 3. RVIT, id est immittit. Actiue legatur. |

| [‘FALLS DOWN,’ that is, ‘emits.’ It should be read as an active transitive verb.] |

Hilary will even offer more general observations about the possible uses of certain Latin words (5), or the ways that Latin has changed in the centuries between Virgil’s age and his own (6):

| 5. ‘Liquitur’ testante Prisciano uerbum defectiuum est, et non inuenitur, nisi ‘liquitur’ et ‘liquuntur.’ |

| [As the grammarian Priscian says, the verb ‘to melt’ is defective and only exists in the forms ‘it melts’ and ‘they melt.’] |

| 6. Antiqua grammatica est ‘temperat mihi,’ moderni enim ‘temperat me’ dicunt. |

| [Ancient usage says, ‘I give restraint to myself,’ but nowadays we say, ‘I restrain myself.’] |

Hilary’s implementation of tools from formal logic to explain features of the Georgics also helps to better place his commentary within the milieu of twelfth-century northern France, where scholars such as Peter Abelard and Peter Helias further developed traditional theories of grammar by blending them with Aristotelian logical terminology. Hilary regularly employs logical phrases such as cause and effect (7), genus and species (8), essence and accident (9), and identifies various types of formal arguments (10), as demonstrated by the following samples:

| 7. SITI, calore. Effectus pro causa est. Est enim sitis effectus caloris. |

| [‘THIRST,’ that is ‘heat.’ Virgil lists an effect in place of a cause. For thirst is the effect of heat.] |

| 8. PADO illo fluuio. Species pro genere. |

| [‘THE PO,’ that is, ‘the river.’ Virgil puts a species in place of a genus.] |

| 9. PINGVIS HVMVS DVLCI VLIGINE. Vligo est naturalis humor terre. Adest illi quidem inseparabile accidens. |

| [‘EARTH RICH WITH SWEET MOISTURE.’ ‘Moisture’ is the natural wetness of the earth. Moisture is present to earth as an inseparable accident.] |

| 10. NONNE, argumentum est a maiori. |

| [‘ISN’T.’ This begins an argument from a major premise.] |

Lastly, throughout the commentary, Hilary displays a characteristically twelfth-century mastery over the Latin colores rhetorici: literary phrases taken from the ancient Roman study of rhetoric, which we might term today ‘figures of speech.’ Rhetorical terms that Hilary employs in order to explain the syntax of Virgil’s poetry include: pleonasm, metaphor, captatio benevolentiae, hypallage, litotes, tmesis, ecbasis, repetitio, parissologia, occupatio, epexegesis, antonomasia, use of epithets, and discussion of poetic license. Some of these colores will be familiar to a modern audience, while others are more obscure and witness to the great importance of formal rhetorical training in the cathedral schools of medieval Europe, itself a testament to the received legacy of ancient Roman oratorical education.

Considered together, these three approaches to literary explication (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) make up a significant portion of Hilary’s teaching/scholarship and reflect the approach to poetic exposition cultivated in the antique Greek and Roman grammar schools.

In addition to such exercises, which facilitate a lower-order understanding of the Georgics, Hilary’s commentary encourages a deeper analysis and evaluation of the text. In the first place, Hilary divides (11), categorizes (12), and assesses textual information (13) in order to provide insight into the structure of the poem (14):

| 11. AMAROR, id est amaritudo, TORQVEBIT TRISTIA ORA TEMPTANTVM SENSV, id est gustu. Quidam libri habent ‘amaro gustu. |

| [ ‘BITTERNESS,’ that is ‘bitterness’ (a more common Latin word) WILL DISTORT THE SAD MOUTHS WITH ITS SENSATION, that is with taste. Other manuscripts have ‘with bitter taste.’] |

| 12. NON ALIOS PRIMA non physice, sed poetice dictum est mundum creari in uere, cum ante mundum tempus nullum esset. Tempus enim est mora et motus rerum mutabilium. |

| [‘NOT OTHERS FIRST.’ Virgil does not rely on the natural sciences when he says that the world is created in springtime, but rather employs poetic license, since before the world there was no time. For time is the stopping and starting of all mutable things.] |

| 13. ET FERT SAPOREM TARDVM uix intelligibile est. |

| [‘AND BRINGS LATE SLEEP.’ This is hardly intelligible.] |

| 14. TVQVE. Post inuocationem deorum inuocat Augustum. Non enim sufficit poetis sapientia, nisi adsit sufficientia. |

| [‘AND YOU.’ After the invocation of the gods, Virgil invokes Caesar Augustus. For wisdom is not enough for poets; they also need sufficient wealth.] |

Second, Hilary supplements his understanding of the text with observations drawn from his own culture, which he identifies as European (15), Christian (16), and specifically French (17):

| 15. MARE. Ex oceano, qui terram circuit, profluit Mediterraneum mare, quod diuidit Athlantam – montem illum, qui in Africa est – a Calpe monte, illo qui est in Europa, ubi nos summus. |

| [‘THE SEA.’ The Mediterranean Sea flows out of the ocean, which encircles the world, and divides Atlanta, that mountain in Africa, from the Calpe mountain, which is in Europe, where we are.] |

| 16. TYLE. Tyle insula est oceani ultra Britanniam, in qua sunt decem et novem dies circa Beati Iohannis festam fere sine noctibus, et circa natale Domini totidem noctes fere sine diebus. |

| [‘TYLE.’ The ‘Thule’ is an ocean island beyond Britain, where there are nineteen days around the time of the feast of St. John without any nighttime. And near Christmas there are the same number of nights without any daytime.] |

| 17. SILIQVA, uocatur folliculus quidam, qui intra se leguminis grana claudit, et a uulgo dicitur ‘cossa.’ |

| [‘POD.’ Virgil names a certain shell that contains the grains of legumes. In French we call this a ‘cossa.’] |

All considered, these examples demonstrate how Hilary draws from the long-standing storehouse of grammatical terminology, hermeneutics, and classical analysis of the texts received from antiquity while exploring the agricultural poetry of Virgil’s Georgics and investigating questions pertinent to society in twelfth-century France. Reading strategies inherited by the medieval Latin grammarians from their antique counterparts provided professional scholars with license to bridge both curricula (most famously the liberal arts and Christian biblical exegesis and theology) and competing schools of interpretation within these disciplines. However, these medieval scholars also inserted themselves and their cultures into the stories they unpacked, as in one instance in which Hilary compares his society to that of ancient Greece:

Ascrevm per oppida id est Hesiodum, quia imitatur eum. Hesiodus enim Grecus fuit, unde dixit ‘fontes.’ Greci enim sunt fontes et nos riuuli.

[‘The Ascrean through the towns,’ that is ‘Hesiod,’ because Virgil imitates him. For Hesiod was a Greek. And that is why Virgil says ‘springs of water.’ For the Greeks are the underground springs and we are the rivers that emerge from them.]

Because of this unique blend of ancient pedagogy and broader societal observation and reflection, remnants of medieval teaching, such as Hilary’s reflections on the Georgics, raise interesting questions not only about the content of twelfth-century scholarly commentaries, but also about the context in which students and teachers studied canonical texts together in the cathedral schools of northern France, whose reputation eventually paved the way for the formation of the University of Paris. These school commentaries give us a privileged window into a type of literary education whose aims and internal tensions have something of the perennial about them: striving to be comprehensive yet focused, simultaneously ancient in its methods and surprisingly contemporary in its concerns.