by Katarina Pejovic, Doctoral Candidate, Department for the Study of Religion, University of Toronto

Nov. 2022

I was very delighted to be able to share some intriguing readings with the Practices of Commentary discussion group, and to reflect on and learn alongside such a robust community of erudite scholars. I prepared a short presentation on two papers, both from the same anthology:

- Bailey, Anne E. “Miracles and Madness: Dispelling Demons in Twelfth-Century Hagiography.” In Demons and Illness from Antiquity to the Early-Modern Period, edited by Siam Bhayro, 235-252.

- Ockenström, Lauri. “Demons, Illness, and Spiritual Aids in Natural Magic and Image Magic.” In Demons and Illness from Antiquity to the Early-Modern Period, edited by Siam Bhayro, 291-312.

The source volume, Demons and Illness from Antiquity to the Early-Modern Period, contains twenty chapters ranging from Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt to early modern Europe. Arising out of an international conference held in 2013, it contributes to comparative analyses of medical, cultural, and linguistic conceptions of magic, illness, demons, and bodily performances of health across various cultures, time periods, and histories. The two chapters I selected both deal with magic in medieval Western Europe, complimenting each other with their surveyed texts.

Bailey interrogates what she identifies as the need to separate medicine and religion in late-twentieth century scholarship on medieval medicine. She sees the prioritization of sources that do not involve demons as agents of illness among late-twentieth century scholars as betraying a set of modern preoccupations and agendas, especially in light of the majority of written testimonies for mental and behavioural disorders between late antiquity and 1200 being found in hagiographical narratives of pilgrims being healed. Drawing on twenty of these miracle collections, compiled in England between the years 1080 and 1200, Bailey provides a brief survey of some of the 95 case studies of mental disorders, especially those which attribute supernatural agents, namely demonic causes, as being able to affect and exacerbate particular mental health symptoms. In her conclusions, she notes the remarkable variability of these texts and the presence (or lack thereof) of demons, to note that medical science and religious faith were not opposed to one another in the English medieval period; warning historians not to attempt to untangle them, but rather seek to understand how they come together by considering questions of audience, reception, and mediation.

Ockenström’s piece builds nicely off Bailey’s, considering questions of demonic possession’s presence in natural and image magic—two traditions existing contemporaneously with official demonological accounts from the Church, whose protocols for engaging with and employing demons and other spirits for the purposes of divination, magic, and profit were derived from Judaism and Christianity, but presented more complicated views on relationships (both contractual and otherwise) with these beings. These are genres I am particularly interested in, especially in light of my ongoing doctoral studies on Christianity and magic. Drawing on sources including the famous Picatrix, she considers a dozen texts of image and natural magic in which connections between spiritual beings and illnesses appear, considering the different perspectives from which they treat these beings, protocols for their interactions, associations with herbs, stones, astrological phenomena (especially the fixed stars), and instructions, materials, and iconographical guidelines for their conjuration, subjugation, use in divination and sorcery, and inclusions in talismanic images and enchanted rings. Ockenström’s survey of these materials considers how, while demons are still largely considered to be the adversaries of mankind, connected to stars, planets, and natural phenomena thought to bring misfortune and illness, they may also be summoned intentionally for the benefit of the conjuror, using specific instructions, astrological timings, and material aids in order to compel them into speaking truth and servicing the conjuror without harming them. Special attention is given to texts which locate demons as the causes of illnesses (including illnesses the conjuror can induce in others by the employment of these same spirits); practices whose theological and magical roots can be traced back to earlier Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Egyptian customs; from Hellenistic natural sciences to the Greco-Egyptian Magical Papyri.

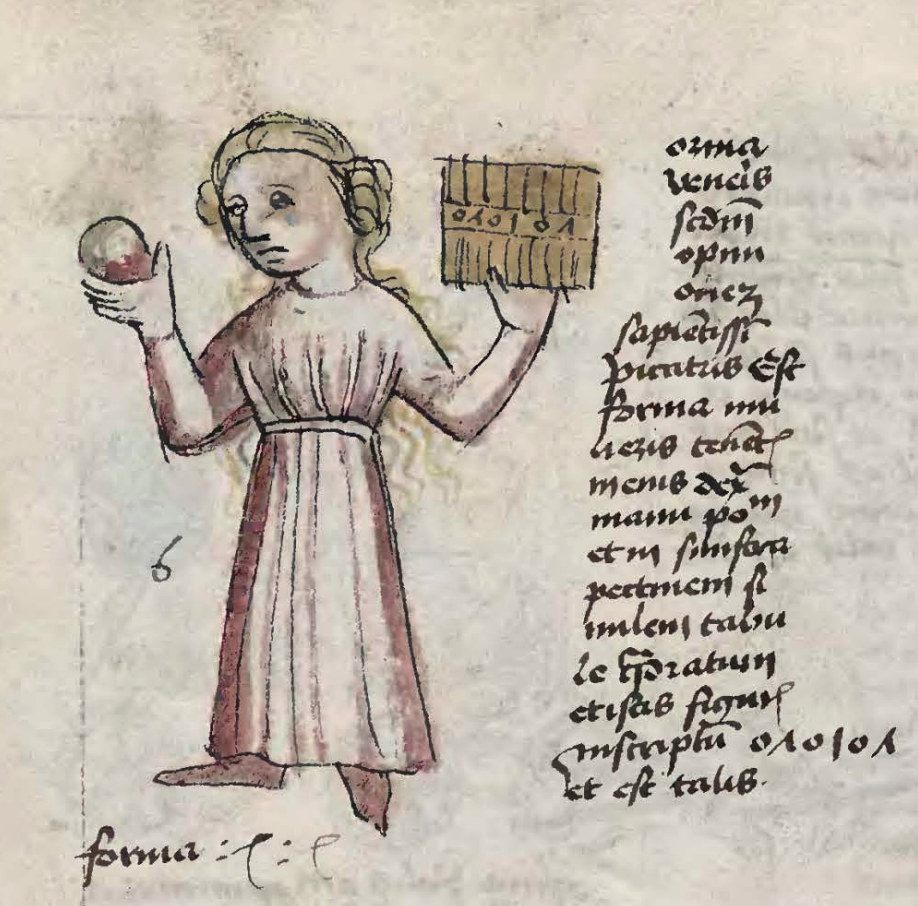

Above image: Biblioteka Jagiellońska, BJ Rkp. 793 III. Image of Venus. Opera medica, astronomica et astrologica. Latin, created 1458/59. Source: http://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/Content/868/PDF/NDIGORP000800.pdf

In our ensuing discussion of these texts, we considered how they both deal with questions of commentary, materiality, and the very concept of “texts”. Questions were raised about what exactly constitutes a hagiography, the financial motivations behind miracle stories (especially as they may drive attention and pilgrimage to the places in which these miracles are performed), and the audiences and reception of the texts Bailey surveys. Prof. Andrés-Toledo directed our attention to the Zoroastrian origins of many of the demons present in image and ritual magic texts, especially as we reflected on the transmission of numerous magical texts, including the Picatrix itself, from Arabic into Latin.

I was greatly appreciative for the opportunity to discuss my own ongoing doctoral research on Cyprian of Antioch, the famous sorcerer-saint, and the transmission of his legends from the Mediterranean and Balkans into Spain, Portugal, and South America. Our discussion closed around a few questions concerning orality, the construction of the “magical text” and grimoire, and Cyprian’s enduring construction as a site of meaning-making and negotiation of licit and illicit displays of ritual power. I am sincerely grateful for the opportunity to share these texts and discuss my own work, and to connect with scholars from so many rich and diverse fields.