by Megan Bryson, University of Tennessee

Among the various technologies that circulated in the medieval world were Buddhist modes of statecraft that promised to strengthen rulers’ power over their territory. One of the key manuals for strengthening Buddhist statecraft in the Sinosphere, meaning the parts of Asia that adopted Chinese script, was the Scripture for Humane Kings (full title: Perfection of Wisdom Scripture for Humane Kings to Protect Their States). This text was probably composed in northern China during the fifth century, and then revised in the Tang dynasty (618–907) by the tantric Buddhist master Amoghavajra (Bukong in Chinese; 704–774).

Both versions of the scripture generated commentaries, subcommentaries, ritual texts, and visual art in Tang China, Koryŏ Korea (918–1392), Heian Japan (794–1185), the Khitan Liao dynasty (907–1125), and the Tangut Western Xia dynasty (1038–1227). The Tang court sponsored recitations of the scripture to dispel invasions; in Heian Japan, maṇḍalas based on the scripture and its ritual texts became the foundation for state protection rites; and in the Western Xia monastic ordinands had to master the recitation of the Scripture for Humane Kings whether they read Sinitic script, Tangut, or Tibetan.

The Scripture for Humane Kings also found favor in the kingdom of Dali (937–1253), centered in what is now southwest China’s Yunnan province and surrounded by the Song dynasty (960– 1279), Tibet, Pāla India (750–1174), Bagan (1044–1287), and Đại Việt (1010–1225). Dali’s location suggests cultural hybridity, and Buddhist visual and material culture circulated in Dali across multiple routes. Though several Dali-kingdom manuscripts include mantras and syllables in Sanskrit Nāgarī script (some of which indicate direct contact with northeast India), the Dali kingdom’s textual corpus shows a stronger orientation toward Sinitic Buddhism. In encounters with the Song-dynasty court or its emissaries, Dali representatives repeatedly sought to trade their prized horses for texts, including many Buddhist scriptures.

Most of the Buddhist texts that survive from the Dali kingdom were discovered in 1956 at Dharma Treasury Temple, located to the southeast of Er Lake in the Dali plain. Dharma Treasury Temple had been the family temple of the Dong clan who served as Buddhist ritual masters at the Dali court. In addition to preserving seven unique Dali-kingdom texts, Dharma Treasury Temple also includes manuscripts of Tang-era Sinitic translations of widely known scriptures as well as commentaries.

Amoghavajra’s version of the Scripture for Humane Kings was among the most important texts for the Dali court: two partial manuscripts of the scripture survive with commentary and subcommentary; a 1052 abridged copy of a tenth-century subcommentary known as the Compass for Protecting the State Subcommentary has only been found in Dali; there is an extended section on the “State-Protecting Prajnā Buddha Mother” in the 1136 ritual text Rituals for Inviting Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Vajra Beings, Etc. found only in Dali; and the 1170s Painting of Buddhist Images (Ch. Fanxiang juan) includes multiple scenes based on the scripture.

Of the various ways in which Dali court Buddhists mobilized the Scripture for Humane Kings, the commentary and subcommentary have stuck with me the most because of their illegibility. The two partial manuscripts, now both housed in the Yunnan Province Library, feature two kinds of annotation and subcommentary that defy easy interpretation: some of the characters abbreviate established characters, but others appear to be unique to the Dali region. How do we make sense of this commentary when we can’t make sense of this commentary?

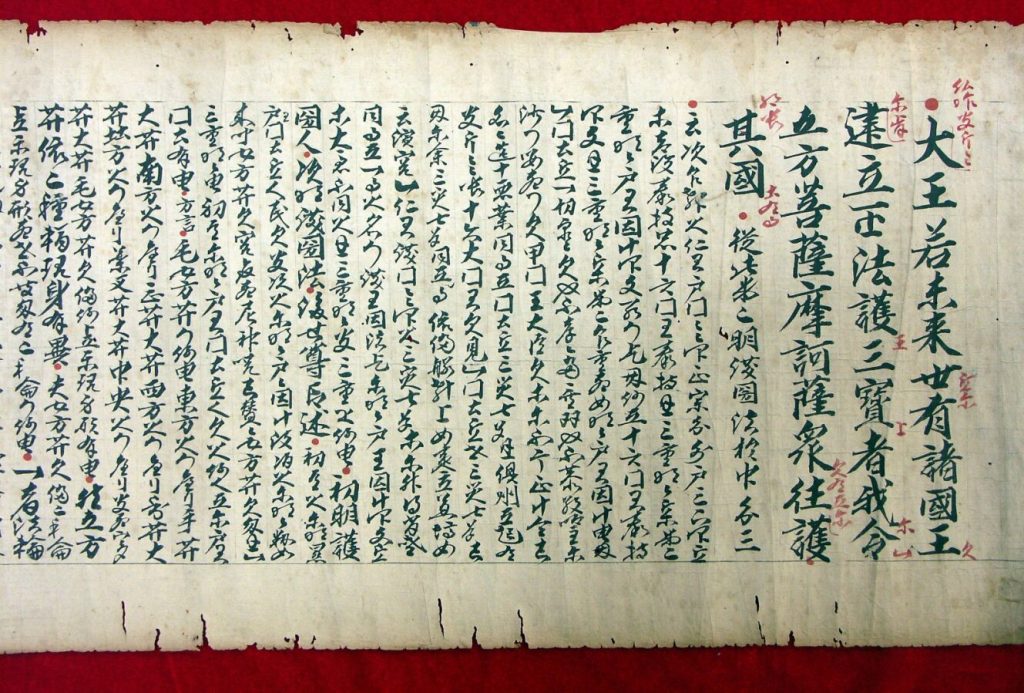

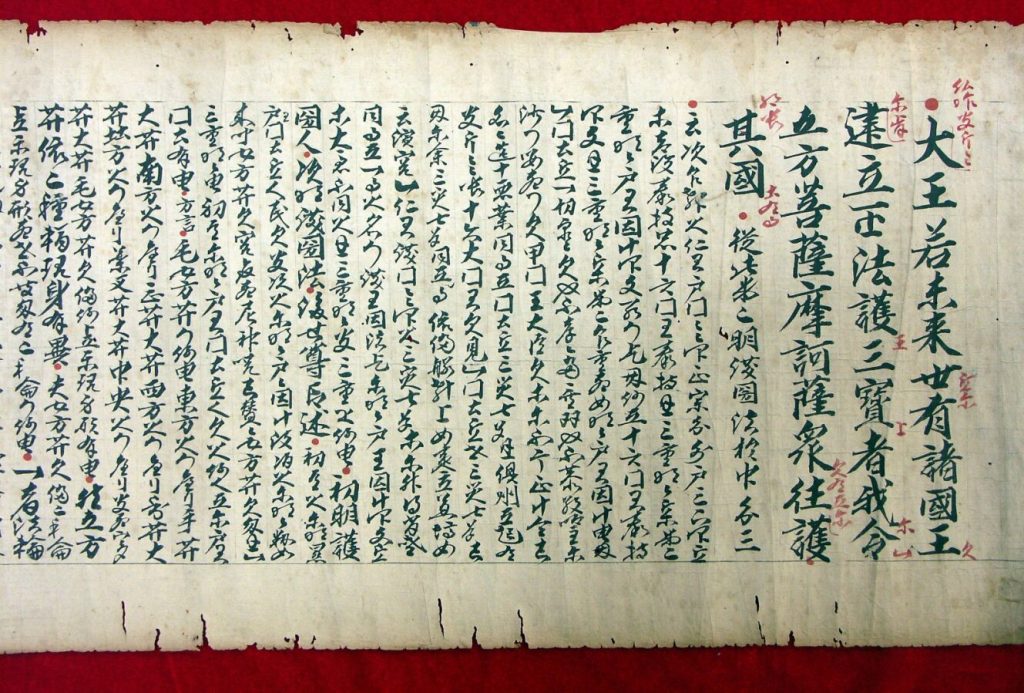

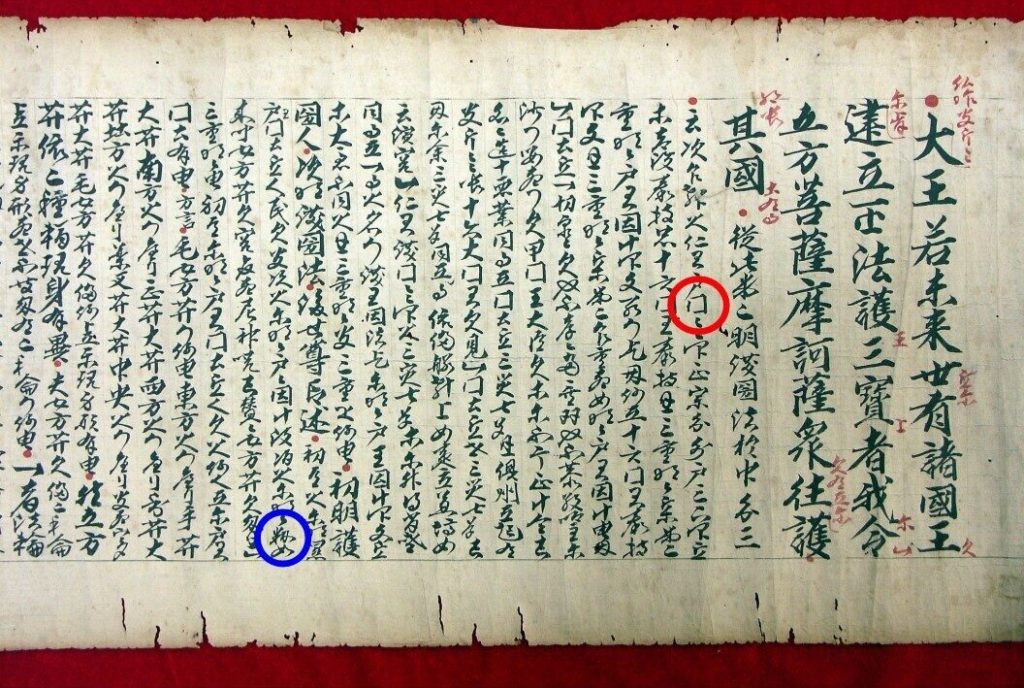

I’ll start with an example from the second partial manuscript of the Scripture for Humane Kings, which is in the scroll format and measures 30.2 cm tall by 10.35 m long. Though the manuscript’s material has not been recorded, it is likely made of mulberry paper, the most common substance for Dali-kingdom texts. This section of the text discusses the five bodhisattvas who protect kings who follow the scripture.

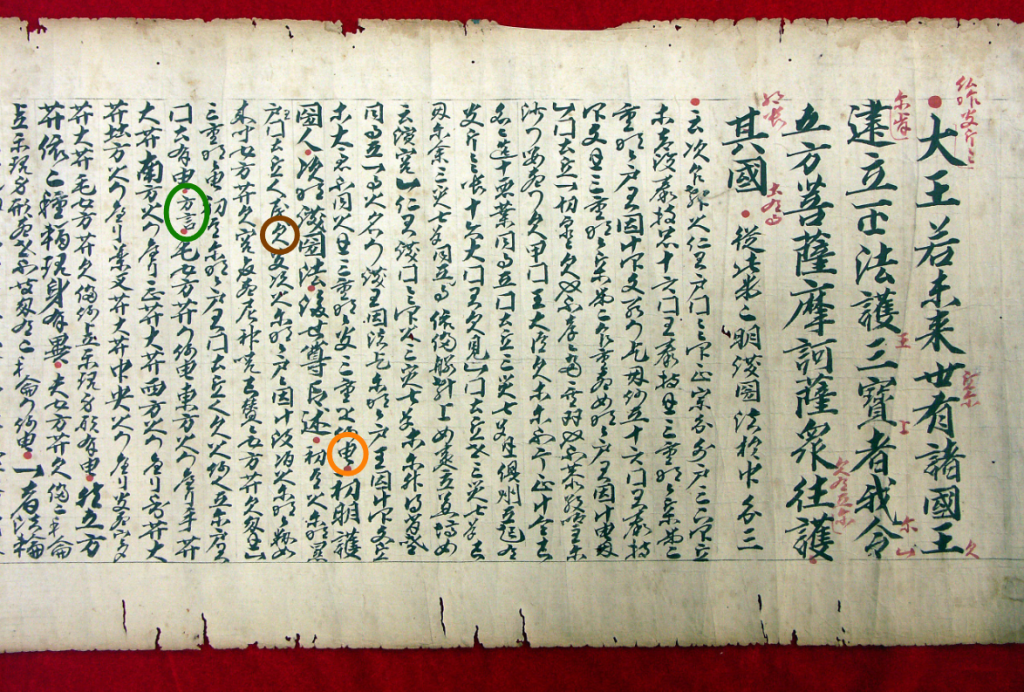

The scripture text (marked in green) is written in larger, regular script; Liangbi’s commentary text (marked in blue) is slightly smaller and more calligraphic; and the subcommentary (unmarked) is even smaller and more “cursive.” This aligns with practices of commentary in Tang-dynasty Buddhism, which shows the strong connections between Dali manuscript culture and Chinese manuscript culture more broadly.

Here the scripture text, excluding the red annotations, states, “Great king! I will command the bodhisattva-mahāsattvas of the five directions to assemble and go to protect any state wherever and whenever in the future the kings of states establish the Correct Teaching and protect the Three Jewels.” Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas are beings who have decided to postpone their final awakening to save others first; the Correct Teaching and Three Jewels both refer to Buddhism.

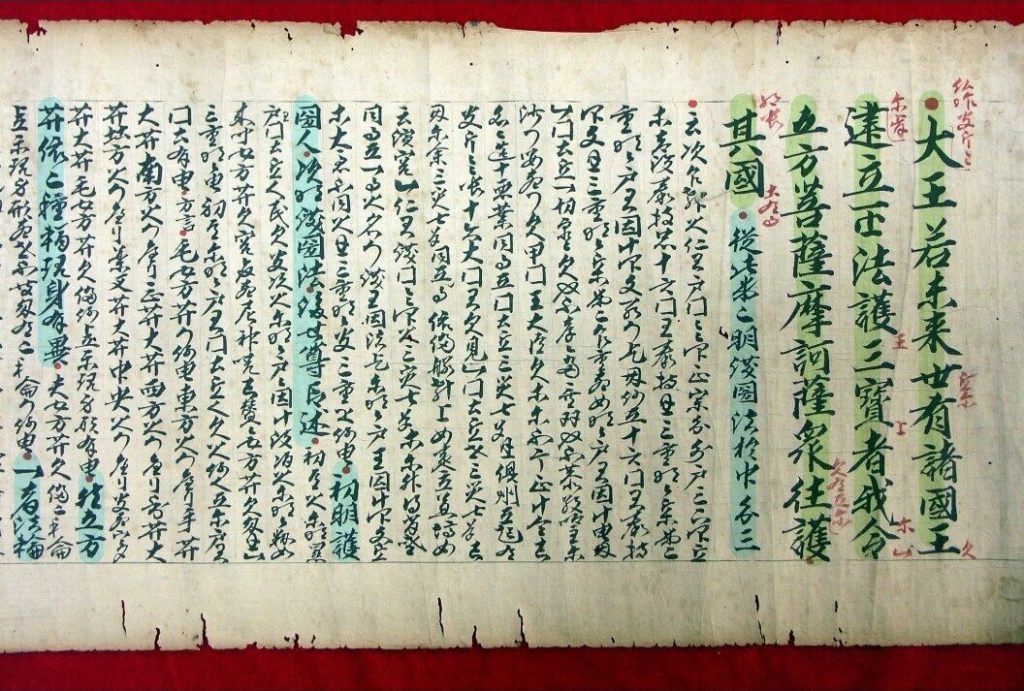

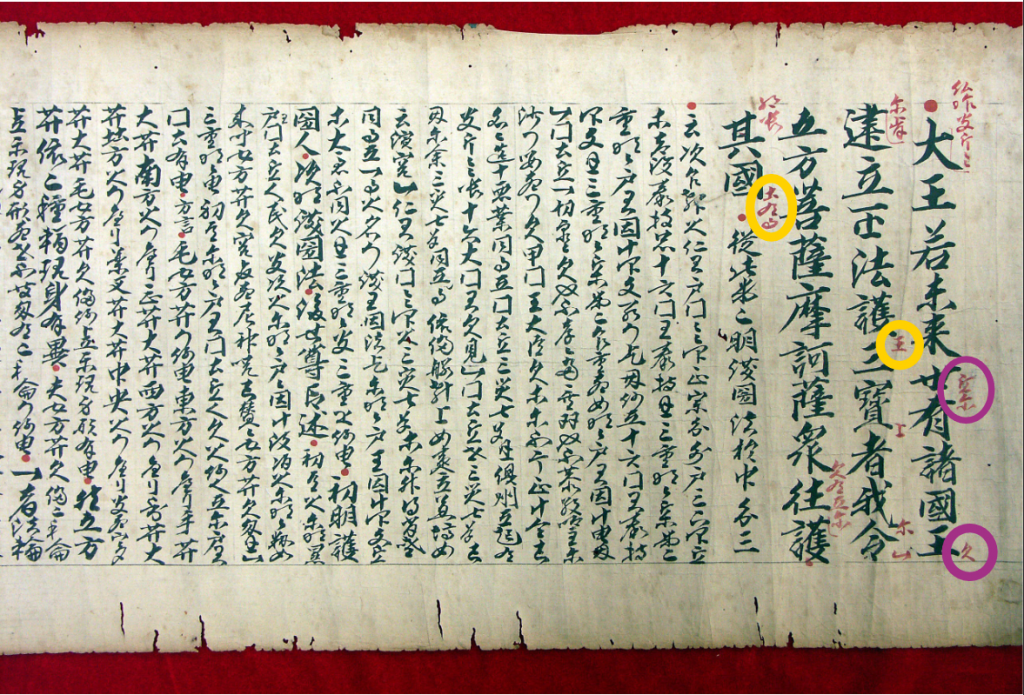

The red annotations to the right of the main text add two different kinds of information. Some, like the terms circled in purple, seem to introduce grammatical markers. The first purple circle includes a character that often appears after locations; the second purple circle includes a character that appears after people (here, kings). Other annotations, like the terms circled in yellow, expand or change the meaning of the words. For example, the original text reads “protect the Three Jewels,” and the added character, “king,” changes the meaning to “protect the king’s Three Jewels.”

A line of Liangbi’s commentary follows the scripture text, though Liangbi is actually discussing the previous line in the scripture. The commentary here concerns the scripture’s structure rather than the specific contents: “From here, the second part illuminates the methods for protecting the state, which are divided into three sections.” The extensive subcommentary that follows is not fully legible to me, but it follows Liangbi’s focus in outlining the different sections of the current chapter, “Receiving and Keeping This Scripture.” The subcommentary also calls back to a previous section of the scripture and commentary that blames the country’s misfortunes on the people’s lack of respect for their parents, teachers, rulers, and officials.

The two kinds of “irregular” characters are on display in this section. Instead of giving the full character for “country,” which is usually written as a box with the character for “territory” inside of it 國, the subcommentary usually writes only the box: 囗 (circled in red). This kind of abbreviation appears frequently throughout the subcommentary and interlinear annotations; it is still fairly legible for readers who are proficient in Chinese script. Another kind of abbreviation found in this manuscript involves combining parts of two characters to form one single character. For example, the name of the historical Buddha is Śākyamuni, and the first part of this, Śākya, is usually written with the two Chinese characters 釋迦 (Shijia in Mandarin). In this manuscript, however, the two characters become the single character 米加 (circled in blue).

For the Dali court Buddhists who copied and read these manuscripts, the subcommentary’s abbreviations would have operated like a shorthand. Even for those of us far removed from the Dali court, proficiency in reading Chinese script and familiarity with Buddhist texts allows us to fill in most of the gaps. This is not the case, however, for the other kind of unusual script we find in these manuscripts.

The subcommentary in the partial manuscripts of the Scripture for Humane Kings contains many characters that resemble standard Chinese characters, as well as some that do not correspond to any known character (including variants). Many of these characters appear to fulfill grammatical functions, such as the character resembling 欠 (circled in brown) that appears after references to people (perhaps as a counter), or the final character 电 (circled in orange) that ends sentences. In two places the subcommentary includes the label “dialect” (circled in green), but, given the widespread use of these characters, it remains unclear why the “dialect” label only appears twice.

Dali-kingdom scriptures’ unusual characters have generated scholarly debate: some scholars read these characters as mere abbreviations of more complex characters, while other scholars treat the unusual characters as early evidence for writing the language of the Bai ethnic group, which is centered in the Dali region. Unlike other polities that existed at the same time as the Dali kingdom, such as the empires of the Jin, Liao, and Tangut Xia, the Dali court did not develop its own script. When a writing system called “Bai script” does show up in the mid-fifteenth century, it uses and adapts established Chinese characters to the local language. While it would be anachronistic to refer to the unusual characters in Dali-kingdom scripture subcommentaries as “Bai,” given the lack of ethnic discourse circulating at the time, the subcommentary script does appear to represent a different language than classical Chinese.

What, then, do the Dali-kingdom subcommentaries on the Scripture for Humane Kings tell us about practices of commentary?

First, the act of sponsoring and composing subcommentaries demonstrates a strong commitment to understanding the scripture itself as well as its commentary. The Dali court sponsored an array of materials related to the Scripture for Humane Kings, including ritual texts and visual art. The commentary and subcommentary remind us that Dali Buddhists also needed to know what the scripture meant.

Second, the scribes who copied the Scripture for Humane Kings distinguished formally between scripture, scriptural annotations, commentary, and subcommentary, using abbreviated and otherwise nonstandard characters only for the scriptural annotations and subcommentary. This suggests a need to preserve the scripture and commentary text in their original form, and to make the different textual registers clear for the reader.

Third, these manuscripts would have only been completely legible to Dali court Buddhists familiar with the local writing system. Considering the common premodern practice of reading aloud, it seems likely that the scriptural annotations and subcommentary were related to orality in some way, even if they do not represent the local vernacular. For example, these markings could be similar to the kundoku readings that allow for readings of classical Chinese texts in Japanese.