by Libbie MILLS, Department for the Study of Religion, University of Toronto

Introduction

For a paper presented at the 2019 Edinburgh meeting of the American Council for Southern Asian Art (ACSAA), I worked through a range of Sanskrit texts

Aṃśumatkāśyapa chapter 96; Aṃśumadāgama 56; Agnipurāṇa 67 and 103; Ajitāgama 73 and 94; Aparājitapṛcchā 49, 50, 52, 109, 110 and 111; Īśvarasaṃhitā 19; Kāmikāgama P32, P58, U33, U34, U35, and U45; Kāśyapajñānakāṇḍa 104; Kiraṇa 63; Tantrasamuccaya 11; Dīptāgama 59; Devyāmata 64; Piṅgalāmata 12; Pratiṣṭhālakṣaṇasārasamuccaya 21; Prāsādamaṇḍana 8; Bṛhatkālottara jīrṇoddhārapaṭala; Mayamata 5 and 35; Mayasaṃgraha 5, along with the accompanying Bhāvacūḍāmaṇi commentary by Bhaṭṭa Vidyākaṇṭha; Mohacūrottara 5; Rauravāgama 44; Vimānārcanakalpa 62, 64, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 76, and 77; Viṣṇusaṃhitā 24; Śilparatnākara 5; Samarāṅgaṇasūtradhāra 44 and 45; Suprabhedāgama 54, 55 and 56 ; Somaśambhpaddhati kriyāpāda 10.

on jīrṇoddhāra, the removal (uddhāra) [and replacement] of the old (jīrṇa), for temples and icons.

While the term jīrṇoddhāra clearly implies a renovation, I veer away from translating it in that way, in order to respect the meaning held by the compound itself, which is that of a removal of what is old. The emphasis on the removal side of renovation, as opposed to the replacement side, holds sense when one reads accounts of the great harm that comes from an old object if it is not removed and disposed of. Of course, replacement will follow removal, and much attention is paid in jīrṇoddhāra literature to how that is carried out, but it is the removal of the corrupting force of an old item that is given principal importance in the labelling of the procedure.

The texts I read each told, on the whole, a similar story, and I was considering how to gather it together for the ACSAA presentation, when I realised that someone else had already done it for me. That someone is Nigamajñānadeva, a 16th C southern Śaiva author of the Jīrṇoddhāradaśaka, “Ten Verses on Jīrṇoddhāra”. The text is accompanied by a Vyākhyāna commentary by the same author, and quotes drawn from a wide range of predominantly Śaiva sources. Having used the structure of the Jīrṇoddhāradaśaka to frame that ACSAA presentation, I went on to study the text more closely, using twelve manuscript copies held at the Institut Français de Pondichéry (IFP)

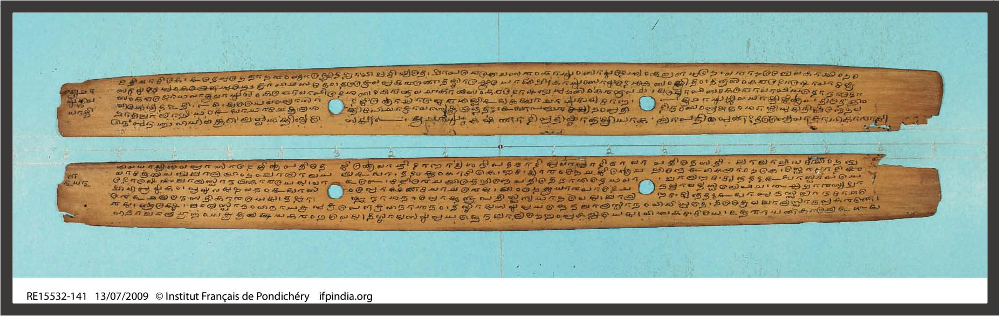

The manuscripts I used were: RE 04073b, RE 15532b, RE 15535k, RE 30483f, RE 30485a, RE 33704ab, RE 37009a, RE 37072p, RE 38307a, RE 45814, RE 39808p, RE 38365bc. Manuscripts held by the IFP are clearly digitized, with a good search engine. It is a joy.

One begins a search here: https://www.ifpindia.org/digitaldb/online/manuscripts/login.php.

to make a critical edition and English translation of its telling of the principles of jīrṇoddhāra, along with supporting portions of its Vyākhyāna commentary. In making the edition, I hoped to facilitate access to this text that elegantly assembles a long textual tradition of maintenance theory into a clear framework of ten verse points. The material is both of use in looking back over the tradition and, since it remains in active use, also of relevance to an understanding of contemporary maintenance practice. The verses tell us how temples and idols have been, and continue to be, maintained, and give us the rational for the process.

Text Structure: Verse and Commentary

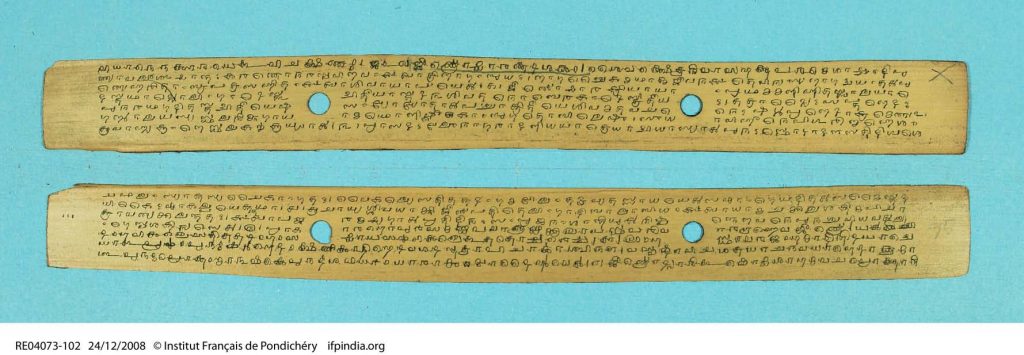

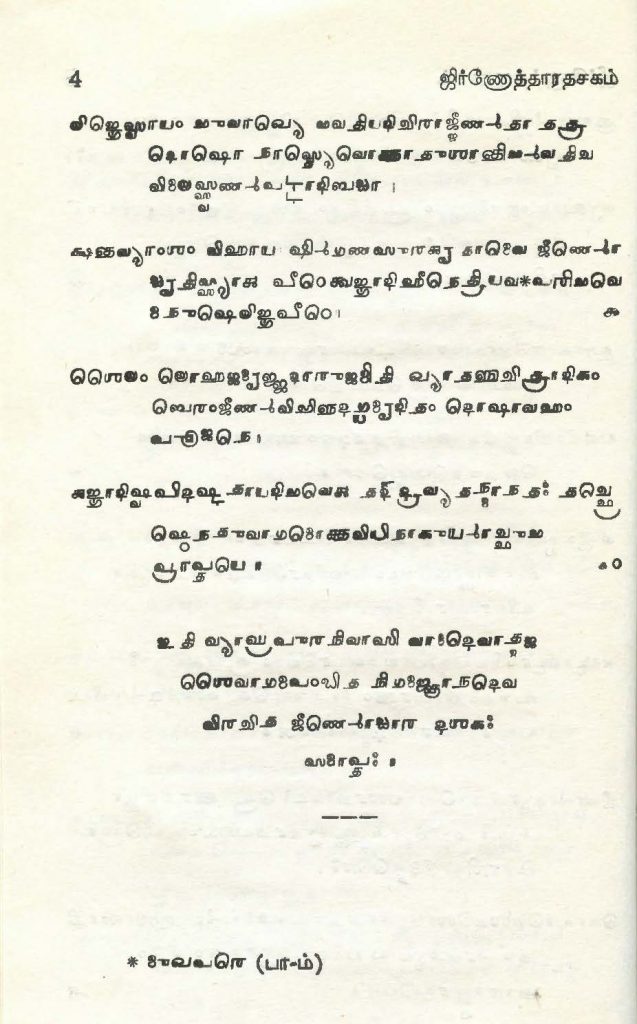

The structure of the Jīrṇoddhāradaśaka has three levels. In the first level, jīrṇoddhāra is explained in just ten verses. Here you see them as they are given in IFP manuscript RE 04073b:

Below you see the complete manuscript RE 04073. The 10 verses of the Jīrṇoddhāradaśaka are to be found at the very bottom of the stack of bundled folios.

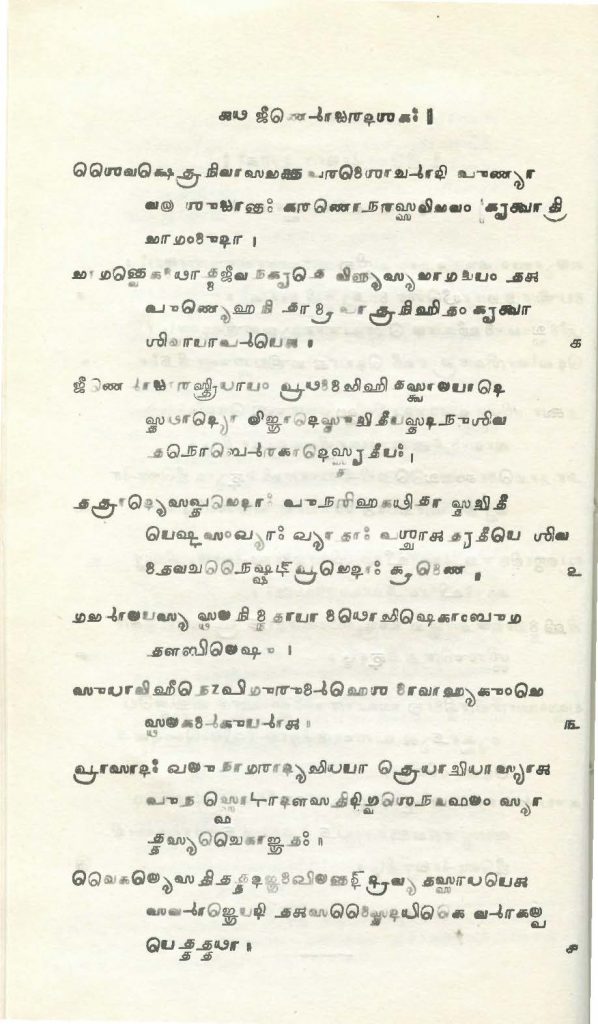

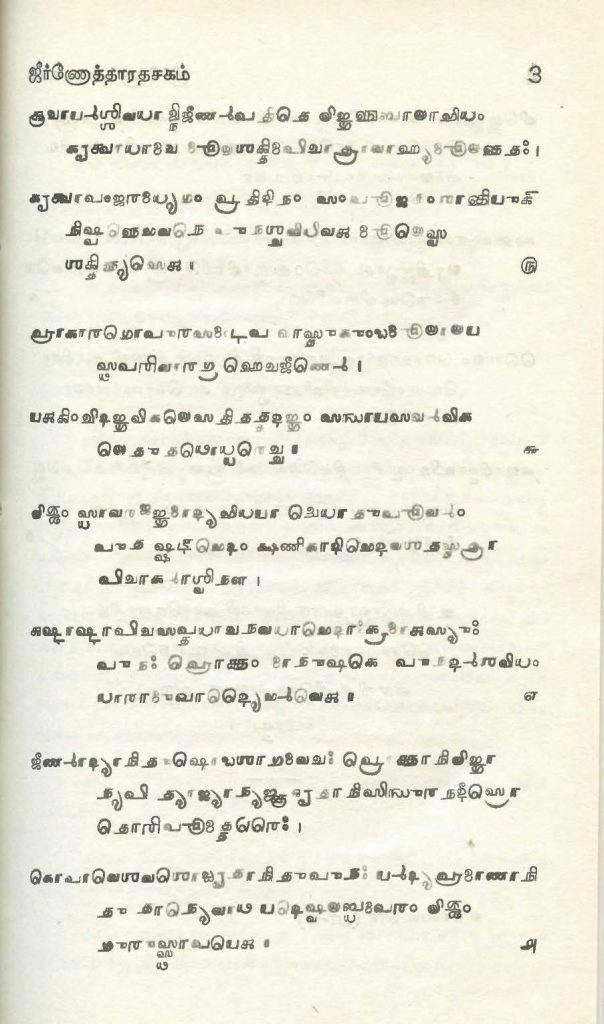

And here are the 10 verses of the Jīrṇoddhāradaśaka as they appear at the beginning of the 1980 edition:

The verses are concise, and packed with references to ideas that need to be unpacked to be understood. Therefore there is a second level, in which each verse receives an explanatory commentary. In a third level, that commentary is backed up and fleshed out with quotes from other authorities. This being a text for devotees of Śiva, the authorities used are largely Śaiva ones.

The quotes are cited as coming from 32 sources: Aṃśumat, Aṃśumatkāśyapa / Kāśyapa, Ajitāgama, Anala, Āgneyapurāṇa, Ādityapurāṇa, Kāmika, Kāraṇa, Kiraṇa, Kriyākramadyotika, Dīpta, Niśvāsa, Bṛhatkālottara, Makuṭa, Mānasāra, Māhāviśvakarmīya, Mṛgendra, Mohaśūrottara, Yogaja / Yogala, Raurava, Vātula / Vātuḷa, Vāstuvidyāprakāśa, Vīratantra, Vaikhānasa, Śilpa, Śivadharma, Śivadharmottara, Sarvajñānottara, Siddhāntasaṃgraha (Trilocanaśivācārya in the Siddhāntasaṃgraha), Suprabheda, Sūkṣma, and Skandakālottara.

Once one has read all three levels – the ten verses, the commentary and quotes – the ten verses alone can work as a point-form precis of jīrṇoddhāra practice as taught in the Śaiva tradition.

The verses run through their topic like this:

Verse 1 Service to god includes jīrṇoddhāra

Verse 2 Jīrṇoddhāra is of three kinds: of temples, of liṅgas, and of the body of Śiva in statue form, etc.

Verse 3 The jīrṇoddhāra of the temple foundation

Verse 4 The role of the builder in jīrṇoddhāra of the temple

Verse 5 The role of the ritual officiant in jīrṇoddhāra of the temple

Verse 6 The jīrṇoddhāra of built items extra to the temple itself

Verse 7 Categories of liṅga

Verse 8 The jīrṇoddhāra of the liṅga

Verse 9 Exemptions from jīrṇoddhāra of the liṅga

Verse 10 The jīrṇoddhāra of the body of Śiva in statue form, etc.

The third category of jīrṇoddhāra, that of the body of Śiva in statue form, etc., is subdivided into six categories, according to the those of: [1] statue, [2] drawing, [3] likeness, [4] trident, [5] fire-pit and [6] Śaiva text. So it is broad, beginning with the body of Śiva in statue form, and ending with that in the form of a text.

The inclusion of disposal and replacement of texts is of particular interest to us, as we look at how texts are formed and commented upon, but no more is given on the subject, except post verse 10, where the commentary introduces a quote to describe the procedure for it:

jīrṇāgamaṃ tat siddhāntapustakaṃ syāt ghṛtāplutam

agnikuṇḍe tu hotavyaṃ hutvāghoraśataṃ japet

The worn āgama, a siddhānta text, should be sprinkled with ghee and offered as an oblation in the fire pit. Having offered it, one should recite the Aghora mantra 100 times.

It is this point-form effect that is the feature of the text that I would like to comment on here.

Commentary as Footnote?

Verse as Title? Highlighter?

Equation.

Since the commentary is by the same author as that of the verses, it works much like expansive footnoting. So expansive, in fact, that there is no room for it at the foot of anything: more fatnote than foot. The scant 10 verses that remain in the main flow of the discourse serve rather like titles to sections. Or, since they give a fuller summary of the content than a title generally would, the sort of assistive eye-catch that one seeks from a highlighter pen.

The highlighter thought might leave one wondering whether the verses came before or after their commentary. But obscurities in the verses stop one from going any further with that thinking. If the commentary is needed to explain the verse, the verse is likely to have come first.

As an example, I give the case of the word ca at the end of verse 6. This verse concerns the maintenance of built elements that are extra to the temple itself: the boundary walls, gateways and peripheral shrines, and so on.

prākāragopurasamaṇḍapavāstukuṇḍamūlālayasthaparivāragṛhe ca jīrṇe

yatkiṃcidaṅgavikale sati tattadaṅgaṃ sandhāya sarvavikale tu tathoddharec ca

When the boundary wall, gateway, pillared hall, site, firepit or peripheral shrine are worn out, if a part is deficient, one should repair that part, but if the whole is deficient one should remove it [and rebuild it] as before.

Substantial commentary follows, expanding on the verse, glossing each technical term, and supplying practical additional information, such as that given in square brackets in the English translation. The commentary ends with an explanation that the very last word, the ca, “and”, indicates that there is also no fault in rebuilding with better materials and measurements than were previously used, in making something better than before. This must surely be a piece of opinion from the commentary that is secondary to the verse. Were the verse to be drawn from the commentary, the rather important permission to rebuild bigger and better would not be secreted away in the word “and”.

Don’t you agree?

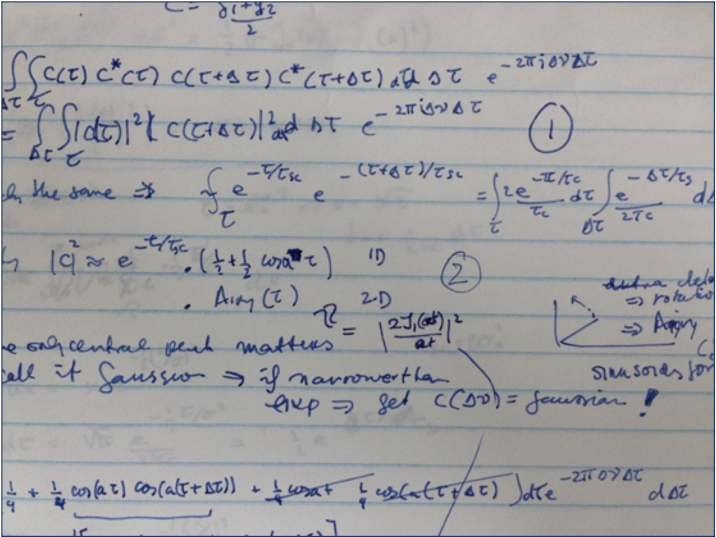

Given the density of the verses, they could perhaps be likened to mathematical formulae, tightly compact, each number or letter mapped to the other, the correct result dependent on a correct following of the track set out. The symbols and patterns of it may be, in part, common-or-garden, requiring no comment. But where they are more obscure, or specific to their case, or holders of sufficient encoding, they will require an explanatory narration.

Marking the Shift from Verse to Commentary and Back

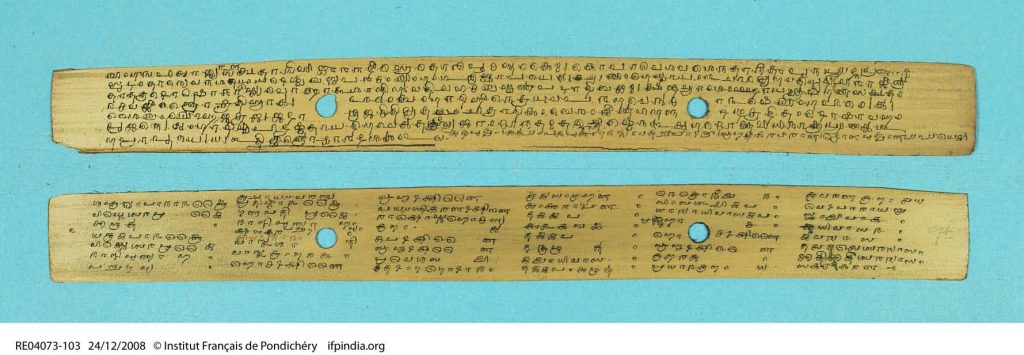

In general, Sanskrit manuscripts give quite subtle markings to warn us that we have shifted from verse to commentary, or the other way around. Below, you see an example of both transitions in manuscript RE 15532. After several folios of commentary on verse 4, verse 5 begins discretely, in the upper level, at line 4, just to the right of the right-hand string hole. It ends on line 6, to the right of the left-hand string hole. There is a discrete loopy line to mark the transitions at each end of the verse. Embedded in its explanation, the verse is not made to stand out very much.

Nothing out of the Ordinary

It might seem an odd thing, to write a commentary on one’s own work. But this is not an uncommon behaviour in Sanskrit scholastic literature. And once one has read a piece like this, one comes to see the charm of it, and to feel some jealousy for the bi-level writing it frees up. There is, here, a sense of liberty to explore, space to go on, that the polite brevity of a footnote will never give, crushed as it is to the bottom of the page, or the end of an article, chapter, or book. It makes you wonder why we don’t do this too, why we constrain ourselves as we do, why, with all the formatting tools available to us, we tamely tread on through the paragraphs.

A Neutral Voice

And there is another good trick here: the commentary never alludes to the common authorship. We do not get: “What I meant by X is Y”. There is a nice neutrality of eye, a dryness to the received: “What is meant by X is Y”.

There is a string of sequences of this type in the commentary to verse 8:

By sindhura is meant a mad elephant or a wild elephant (sindhuro: mattagajo vanagajo vā).

By nadīsrotas is meant a river current (nadīsroto: nadīpravāhaḥ).

By ripu is meant enemies, Turks, etc. (ripavaś: śatravas tuluṣkādayaḥ).

By unmattakaiḥ is meant by those overcome by bile or demons (unmattakāḥ: pittapiśācagrastāḥ etaiḥ).

The author leaves enough distance between his layers of writing to allow him to point critically to what is missing from the verses, what needs to be supplied. That distance is set by the use of the third person of “Next he will tell us about Z”.

An example occurs in the commentary to verse 4:

evam ekāṅgavaikalya uddhāraprakāram uktvā sarvāṅgavaikalya uddhāraprakāram āha.

Having thus is described the process for the removal in the case of deficiency in a single part, he gives the process in the case of deficiency in every part.

Thus does Nigamajñānadeva stand back and reflect on what he has versed up, unfolding it for the receiver.

Filling in the Blanks

And a lot needs supplying. Some of the most important information is held in the commentary and quotes, rather than in the verses.

An example that comes to mind is the treatment at verse 8 of the removal of a faulty liṅga:

jīrṇādyāni tu ṣoḍaśāgamavacaḥproktāni liṅgāny api

tyājyāny ajñakṛtāni sindhuranadīsrotoripūnmattakaiḥ

kopāveśavaśoddhṛtāni tu punar yady avraṇāni sphuṭam

tāny evātha yad eṣv alabdham aparaṃ liṅgaṃ guruḥ sthāpayet

The sixteen liṅgas that are taught in the āgamas as worn out, etc. are to be removed, as are those made in ignorance. And those upraised on account of the onset of rage, by mad elephants, river currents, enemies, or the deranged [should also be abandoned if damaged].However, as long as they are clearly undamaged, the officiant may [re-] establish them. And the officiant should establish another liṅga for any of them that has not been retrieved [within twelve years].

Again, the parts of the English translation in square brackets are supplied by the commentary. Useful, for example, to know how long one may wait before one replaces a liṅga that has gone missing. And other essential information is added too. While the verse gives us no clue as to HOW we can remove a heavy liṅga embedded in the ground, the commentary gives a quote to let us know that the extraction of the liṅga is managed with the aid of a bull or elephant:

uddhārayet tato liṅgaṃ gajena vṛṣabhena vā

mauñjirajjuṃ samādāya trivṛtaṃ baddhayed dṛḍham

gajenoddhāraṇaṃ cet tu rajjvā gocarmakḷptayā

Then he should have the liṅga removed by an elephant or bull. He should securely tie [the liṅga], using a three-fold mauñji cord.

But if the removal is done by an elephant, it should be with a cord made of cow hide.

A Frame

With both verses and commentary under his control, the author can use the commentary as a natural frame. An introduction is placed in front, connecting sentences lead the reader from one verse to the next, and, while the fat commentary space gives the author permission to expand as far as he wishes, it also permits him to draw things to a close at his convenience.

A case in point occurs at verse 7, which lists the categories of liṅga:

liṅgaṃ sthāvarajaṅgamādyabhidhayā dvedhā tu pūrvaṃ punaḥ

ṣaḍbhedaṃ kṣaṇikādibhedavaśatas tatrāpi cārkāśvinau

aṣṭāṣṭāpi ca saptadhā ca navadhā bhedāḥ kramāt syuḥ punaḥ

proktaṃ mānuṣake punar daśavidhaṃ dhārāmukhādyair bhavet

The liṅga is, first of all, two-fold according to the designation of fixed and mobile, etc. It is also of six types on account of a division into transient, etc. And of those [six types] there may be further divisions in turn: into twelve, two, eight, eight again, seven and nine. In the man-made category there may be declared a further subdivision into ten types: dhārā, mukha, etc.

Here we have many categories in multiple layers. The commentary unzips them all, beginning with the set of six that begins with the transient category, listing it in full as transient, clay, wooden, metal, gem and stone. The commentary goes on to explain that each of those six types is further subdivided, so the transient group has twelve types, the clay group has two, the wooden group has eight, the metal group also has eight, the gem group has seven and the stone group has nine types.

Then we are given a full accounting for all those types. The twelve transient types are: sand, rice grains, cooked rice, river clay, cow dung, butter, rudrākṣa, ash, sandal, kūrca grass, flower garland, and sugar. There may be fruit in the place of rudrākṣa and dough in the place of cooked rice. The two clay types are: baked or unbaked. The eight wood types are: śamī, madhūka, maṇḍūka, karṇikara, induka, arjuna, pippala, and udumbara woods. The eight metals are: gold, silver, copper, bell metal, brass, iron, lead, and tin. The seven gems are: pearl, coral, cat’s eye, diamond, topaz, emerald and sapphire. There are nine stone liṅgas according to whether they are self-arisen, or made by men or different types of divine being. A further ten subtypes of man-made liṅga are given in the many quotes that follow, including the dhārā and mukha categories. The commentary winds things up with a comment on how much more could be said:

ityādi bahu vaktavyam asti. vistarabhayān neha likhyate.

On this topic there is a lot to say. It is not written here, for fear of prolixity.

Here I stop too.

With all thanks to Anusha Sudindra Rao, Mohannad Abusarah, Borong Zhang, and Sloane Geddes, for wrangling fatnotes into a blog.