by Stephen LAHEY

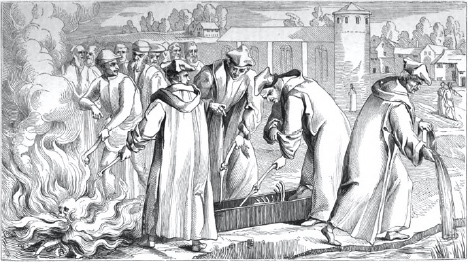

J ohn Wyclif (d.1384) is remembered primarily as a British forerunner of the Protestant reformation, under whose supervision the Bible was translated into English. His writings so angered the fourteenth-century church that his bones were exhumed and burned in 1428, in part because his words inspired the Czech reform movement associated with Jan Hus. Most of Wyclif’s admirers today associate him with the Bible translation; indeed, the Wycliffe Bible Society continues to translate the work into every known language. When I gave a presentation on Wyclif’s philosophy several years ago, a colleague later told me that he hadn’t even known that Wyclif wrote philosophy.

In fact, Wyclif was one of the most original philosophers in fourteenth-century Oxford. It is said that when his ecclesiastical prosecutors encountered his philosophical works, they were astonished at their depth and inventiveness. His reputation as an opponent of the papacy and the ecclesiastical status quo, and his rejection of the coherence of transubstantiation, contributed to the subsequent readiness to dismiss Wyclif’s philosophical works.[1] The Early Modern rejection of scholastic philosophy as needlessly complicated sophistry meant that the milieu in which Wyclif thought and wrote would be forgotten for centuries. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the growth of interest in the history of philosophy, and as the decades passed, the wealth of scholastic thought began to be recovered.

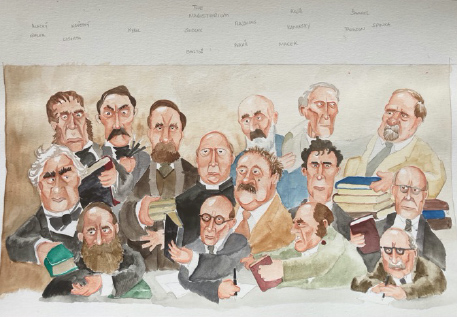

The Roman Catholic church played an important role in this. In the mid-19th century, Pius IX and his successor Leo XIII mounted a theological attack on Modernity, and the scholastic theologian Thomas Aquinas was declared the chief teacher of Catholic thought for a church that refused to accept the hegemony of the Modern. Aquinas’s predecessors, from Augustine of Hippo to Albert the Great, featured in Roman Catholic theology curricula in the first half of the 20th century, and Catholic philosophers began to construct a new scholasticism. In the middle of the 20th century, Thomas and his predecessors were introduced to philosophers outside the Catholic tradition by individuals such as Etienne Gilson, who argued that scholasticism was a tradition well worth the attention of professional philosophers. As time passed, Franciscans began to make convincing cases for members of their order who represented a different approach than that of Aquinas, thereby introducing John Duns Scotus and William Ockham to professional philosophers. The past forty years have seen a growth of interest in the scholastic tradition as it incorporated the differing approaches of Ockham and Scotus into the medieval theological discourse. The scholastic thinkers I’ve mentioned had large numbers of philosophical followers who developed their approaches: for example, Thomists flourished, and still flourish, within the Dominican order of friars, and Scotists do in the Franciscan order. Both have traditions reaching seven centuries back in time, and thanks to the Roman Catholic presence in the conquest of the Americas, and in Spanish colonialism in Asia, branches all over the world.

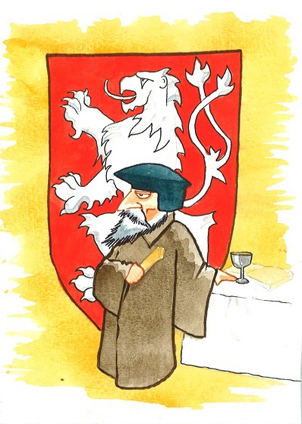

Wyclif attracted attention towards the end of the nineteenth century, thanks to the pan-Slavic movement. A common visual portrayal of the “path to Protestantism” as it was described from the mid-19th century was to portray John Wyclif and Jan Hus as “forerunners” to Luther.

While the Czechs were still subjects of Austria-Hungary, a strongly nationalist movement emerged in Bohemia. Prague had long been the second city of the Empire, but its Slavic identity had long been silenced by German culture and authority. With the Obrození, the Czech National revival stimulated by Josef Jungmann’s Czech dictionary in 1835, the concept of a uniquely Czech identity became popular. The historian Frantisek Palacký presented Jan Hus as the first historical figure to embody this national identity, and Hus quickly became associated with the growing nationalist movement. Konstantin Höfler worked vigorously to disprove this idea, publishing a large number of his editions of important documents from the Bohemian reformation. In 1884, the German theological scholar Johannes Loserth published Wiclif und Hus, in which he argued that all that the Czechs identified as peculiar to Hus was, in fact, simply copied from Wyclif, whom Hus admired. Loserth was one of a number of German and English scholars who had begun to develop modern editions of Wyclif’s theological Latin works, to establish a strong Anglo-Saxon presence in the birth of Protestantism.

Czech scholars responded to Loserth with bitter arguments emphasizing the uniquely Czech nature of the Hussite movement, and in the process, an interest began to develop in Prague in the philosophical debates that were going on when Hus was a student. Wyclif’s philosophical works had arrived in Prague shortly after his death, and became quite popular among the Bohemian theology students and masters in the decades that followed. As the Czech scholarship on this period developed, Wyclif’s philosophical thought began to appear important for understanding the genesis of Hussitism in the ideas of Jan Hus, Jakoubek Střibro, and other young reformers in Prague.

Czech medieval scholarship throughout the 20th century featured attention to the relation of Wyclif to Hus, but the Soviet dominance that began in 1948 directed the studies away from philosophy and towards what was regarded as “proto-Marxism” in Wyclif. During the course of these decades, few Czech scholars pursued Wyclif`s philosophy. Vilém Herold, Ivan Mueller, and František Šmahel devoted themselves to the task, and developed a picture of the Wyclif school in Prague that preceded the death of Hus in 1415. Foremost in that school was a man remembered in the Czech lands for his subsequent opposition to Hus, Stanislav of Znojmo (d. 1414).

Stanislav’s story is one of wrongful neglect. Before 1409, he had been the leader of the Bohemian Wyclif school, writing remarkable commentaries on Wyclif`s works and giving well attended lectures on Wyclif`s thought. As his students became increasingly critical of the Church in Prague, and of the results of the Papal Schism, Wyclif’s works became increasingly dangerous, and were finally condemned in 1410. Stanislav had been called, along with his younger protégé Stěpan Paleč, to give an account for himself in Rome, and after being imprisoned in Bologna, recanted from his support from Wyclif. Both Stanislav and Stěpan returned to Prague, prepared to pursue their students’ errors with vigor. Stanislav did so until his death several years later, and Stěpan accompanied Hus to Constance, where he did his utmost to convince the reformer to renounce the position that led to a heresy trial. Hus refused, and died at the stake in 1415. With that, the memories of Stanislav and Stěpan were associated with Hus’s death, and their works were left in forgotten codices in libraries throughout Bohemia and Moravia.

As the controversy between Germans and Czechs continued in the early 20th century, one of the editors of the Wyclif Society published an edition of De Universalibus, a treatise he imagined to be by Wyclif. Wyclif had indeed written a treatise on the subject, but what Dziewicki had edited was Stanislav’s commentary on Wyclif’s treatise. Ivan Mueller edited and published Wyclif’s treatise of that name in 1985, when Wyclif’s philosophical thought was gaining interest among professional historians of philosophy.

I began my doctoral work on Wyclif in 1990, on the advice of my dissertation director A.S. McGrade, a respected expert on fourteenth-century thought. In the years that have followed, my interest in Wyclif led me to the study of the reception of his thought in Prague. After learning Czech, I began to benefit from the research of Herold and Šmahel and their students, and came to recognize the importance of Stanislav in the transmission and interpretation of Wyclif`s thought.

Stanislav’s Works

Pavel Spunar’s catalogue of Czech authors from the late fourteenth and early fifteenth-centuries lists 55 known works of Stanislav, of which 45 survive. These include 11 sermons, 11 questions, 10 theological treatises, 6 expressly philosophical works, and 17 others, of which one, the commentary on Aristotle’s physics, is not Stanislav’s work. Of these, seven theological works and four philosophical works deserve a brief account because of their direct connection to Stanislav’s reading of Wyclif`s works. Our purpose here is to gain a general overview of the subjects to which Stanislav devoted his most attention as a thinker, both before and after 1409.

Works in Philosophical Theology

De Corpore Christica. 1405

This treatise, which appears to be opposed to the remanentist position of Wyclif, has been revealed to have had a more complicated history than first appears. The whole of it is nine chapters long, of which there are 13 manuscript versions. There are two others consisting of only the first three chapters, and two consisting of chapters 4 through 9. Jan Sedlák published an edition of the whole in 1905, along with an interesting article revealing that the treatise is really two conjoined arguments.[2] Hus had commented in a letter that Stanislav had at one time admitted to being dubious about Wyclif’s remanentist views, despite his otherwise great admiration for his thought. In fact, Hus cites a portion of the otherwise lost Sentences commentary of Stanislav comparing Wyclif’s Eucharistic views to being the thorns naturally accompanying any beautiful rose.[3] Sedlák establishes that Hus was not simply being disagreeable about his teacher, who had expressly denied the remanentist position later. In fact, he establishes that Stanislav’s earlier position is conjoined with Jan Štěkny’s anti-remanentist sermon to make it appear that Stanislav was merely giving the other side a fair shake. The telling evidence is that the remanentist section begins with Stanislav`s favorite opening phrase, ‘It would not seem meritless to investigate…’ This appears occasionally throughout his works, frequently as the beginning of a chapter.

Jan Sedlák, Eucharistické traktáty Stanislava ze Znojma Hlidka 23, 1906

Tractatus de Peccato et Gracia. 1410

Stanislav demonstrates his understanding of Wyclif`s moral theology by summarizing and quoting sections from Trialogus and De Mandatis Divinis. These two treatises contain the heart of Wyclif’s conception of what he called the Law of Love. He envisioned a Christian world in which all members of the church lived in simplicity, with regular preaching and pastoral guidance provided by “evangelical lords”, priests aware that their flocks’ salvation depend upon their words and the exemplary lives of Christ. In De Officis Pastoralis Wyclif had argued that preaching had more salvific power, and contained as much capacity to administer grace, as any of the seven sacraments. Naturally this meant that Wyclif’s theology of grace was a departure from the sacramentally ordered position common in medieval Christianity. He regarded himself as directing religious teaching away from the inventions of recent times, and back to the moral curriculum established by the Fathers.

Stanislav’s editor, Zuzana Silagová, notes that the treatise stands out as the commentary in which Wyclif`s teachings receive Stanislav’s fullest support. “While Stanislav communicates Wyclif’s teaching in other treatises, it does not completely take over: indeed, he often polemicizes against them. Here it appropriates word for word entire passages from De Mandatis Divinis and Trialogus but in a generally truncated form…” p. xii.

I have a prose summary covering up to p. 39 of 179

De Felicitate

This treatise, among Stanislav’s earlier works, articulates the final ideal human state. It builds from Wyclif’s description of the human condition in De Actibus Anime, moving from a general discussion of the role of faith and the moral virtues in happiness to a topic that Wyclif mentions but does not explore deeply, that of the beatific vision of God. The question of whether and how blessed souls perceive God in paradise had been of considerable interest at the beginning of the fourteenth century, and Wyclif’s philosophical theology, partially consonant with Thomism and Scotism, but in other ways more Platonist, gives Stanislav the opportunity to analyse a theologically interesting problem. Throughout Stanislav’s description of the expansion in our capacity for joy and understanding, he touches upon some of Wyclif’s favorite talking points, including the need for recognizing the reality of universals, the need for a skilled preacher to be sensitive to the varying kinds of predication used in Scripture, the indivisibilist understanding of time, and the threats posed by clerical abuses. The treatise draws on Wyclif’s understanding of the nature of the soul and its union with the body, and the relation of the intellectual interior self to the exterior physical self as described in De Composicione Hominis and De Actibus Anime.

Stanislas Sousedik, ed. “Stanislai de Znoyma: Tractatus de Felicitate” Mediaevalia Philosophica Polonorum XIX 1974 pp. 65-126

I have summarized 1-13 of 19 chapters

De Vero et Falso

This treatise explains Wyclif’s correspondence theory of truth most fully, showing how a true proposition maps onto a truth about being. Wyclif’s position, termed “propositional realism”, holds that what contemporary philosophers call “states of affairs”, or more loosely “facts” are what Adam Wodeham called “complex significables”. These are isomorphic with the true propositions we use to identify them. The true predication of something about a subject needs to be carefully explained, which may not be terribly complex for a statement like “The stone is grey”, but becomes more difficult for statements like “No bat is a fish.” To what does the expressed subject “No bat” refer? Is there something that is “not being a fish”? Wyclif struggles with some of these more difficult questions throughout his philosophical works, which reasoning Stanislav recounts and assesses. In some places, he advances Wyclif’s position to provide answers Wyclif did not perceive, but in others, notably the question of the reality of complex significables, he differs from Wyclif. The only contemporary discussion of this treatise is Gabriel Nuchelman’s description of some of the problems about true conjunctions and disjunctions dating to the mid-1970s.

V.Herold, ed., De Vero et Falso Prague 1973

I have the whole summarized.

De Universalibus

This treatise, initially assumed to have been Wyclif’s treatise of the same name when M.H. Dziewicki edited it and published it in 1905, is Stanislav’s thorough examination of Wyclif’s metaphysics. After a brief discussion of Wyclif’s doctrine of divine ideas, much discussed in Prague at the time, he assesses Wyclif’s doctrine of universals, how they have reality, and how they inhere in their particulars. Problems with Wyclif’s thought on identity and difference, relations between kinds of universals, and the nature of specific properties in a creature’s nature dominate the next dozen or so chapters. Finally, he turns to some more difficult problems with Wyclif’s propositional realism, dealing with necessity and truths about counterfactuals.

M.H. Dziewicki, ed., Iohannis Wyclif Miscellanea Philosophica II London 1905

I have all 21 chapters summarized

Other Treatises

Several other works of Stanislav address Wyclif’s thought, primarily with the intent of refuting it. Stanislav wrote them after his decision to renounce Wycliffism in 1409, and they show a thorough understanding of Wyclif’s positions, far superior to the refutations of other opponents like Thomas Netter of Walden. Still, they cannot be considered commentaries, as they were intended primarily to show the untenability of positions deemed dangerous by the church, and are assessed on dogmatic, rather than philosophical, grounds.

- Tractatus de Ecclesia. 1412

- Jan Sedlak, „Stanislaus de Znojma Tractatus de Romana ecclesia“ Hlidka 16, 1911, vols 11 and 12, pp 83-95; reprinted Miscellanea husitica Ioannis Sedlak KTFUK, Univerzita Karlova 1996, pp. 312-324.

- Tractatus Alma et Venerabilis. 1412

- Johannes Loserth, Archiv für Östereichische Geschichte 75, 1889, 361-416.

- Tractatus de Antichristo contra Mgr. Jacobellus de Misa. 1412

- Unedited, my transcription is from ÖNB 4749 112r-145v, and from Třeboň St.A. A16, 424r-427v

- Tractatus de XLV Articulosa Johannis Wiclef. 1413

- Hardt, De Religionis et Fidei Monumentis, Magnam Oecumenium Constantiensis Concilium III, 1698, pp. 212-335

- Tractatus de Ecclesia contra Hereses 1414

- Unedited, my partial transcriptions from Prague N.K. XIII E 7 195r-252r

Stanislav as Commentator on Wyclif`s Summa de Ente

The two treatises, De Universalibus and De Vero et Falso introduce and present commentary on a broad range of topics associated with Wyclif`s Summa de Ente. In some cases, Stanislav is content merely to explain Wyclif`s position, while in others, he shows the errors he perceives in Wyclif’s reasoning, or carries Wyclif’s reasoning farther than Wyclif did. The following list of chapters in the two treatises describes the chapter topics, and the treatises in the Summa to which they refer. I have placed De Vero et Falso between chapters 8 and 9 of the De Universalibus because the subject shifts from basic ontology in Chapter 8 to questions about how Universals inhere in particulars in Chapter 9. This shift demands sensitivity to the importance of understanding the correspondence theory of truth Wyclif describes in earlier treatises of the Summa regarding propositions about creatures and the truths these creatures bespeak in their existence. Before chapter 8, Stanislav’s discussion is not of particular creatures, but of Divine Ideas and Universals in general. Thereafter, it is important to understand how questions regarding specific natures in individuals, how properties are truly predicated in individuals, and higher order reasoning using these propositions all can be understood to express truth before engaging in answering these questions and doing this reasoning. Hence, Stanislav’s De Vero et Falso fits best here, as I demonstrate in my analysis of the Summa (in progress).

The standard practice in quick reference to the thirteen treatises of the Summa is to refer to the Book and Treatise number normally associated with each treatise. These are:

| Summa de Ente I | Summa de Entre II |

| De Ente in Communi. I.i | De Intellecione Dei. II.i |

| De Ente Primo in Communi I.ii | De Sciencia Dei. II.ii |

| Purgans errores circa Veritates. I. iii | De Volucione Dei. II.iii |

| Purgans errores circa Universalibus I.iv | De Trinitate. II.iv |

| De Universalibus. I.v | De Ideis. II.v |

| De Tempore. I. vi | De potencia Productiva. II.vi |

| De Entre Predicamentali I.vii |

In addition, Stanislav comments on issues discussed in:

| De Materia et Forma. DMG | De Actibus Anime. DAA |

I. De Universalibus commentary

| Part I. | Divine Ideas |

|---|---|

| Chpt. 1. Divine Ideas prior to Universals | II.v |

| Chpt. 2. Multiplicity of Divine Ideas | II.v |

| Chpt. 3 Of What there are Ideas | II.v |

| Chpt. 4 Relation of Idea to Ideate | II.v, II.i |

| Part II. | Universals as Such |

|---|---|

| Chpt. 5 Universals exist in things | I.ii, I.iv, I.i, I.v |

| Chpt. 6 Common Formal Causes | I.v |

| Chpt. 7 Universal Specific Natures | De Materia et Forma, I.v |

| Part III. | Propositional and Metaphysical Truth (De Vero et Falso) |

|---|---|

| Chpt.1 Being as Principle of Unity | I.i, I.ii |

| Chpt. 2 God as Truth for all True Propositions | II.i, II.v, I.iii |

| Chpt. 3 Conjunctive and Disjunctive Truths | |

| Chpt. 4 Truths about Relation and Necessity | I.v, DAA II |

| Chpt. 5 Counterfactuals | II.i, II.ii |

| Chpt. 6 God’s will and Created Truth | II.iii |

| Chpt. 7 Truths about Privation and Negation | II.i, I.iii |

| Chpt. 8 Grammatical Truths | De Logica |

| Chpt. 9 How Grammatical Truths arise | |

| Chpt. 10 Errors in Truth | I.iii |

| Chpt. 11 Falsity | I.iii |

| Part IV | Kinds of Universals (De Universalibus) |

|---|---|

| Chpt. 9 Relation of General and Specific Universals in Particulars | I.v.6 |

| Chpt. 10 Identity and Difference | I.iv…4, I.v.4, DCH 7 |

| Chpt. 11 Specific Difference | |

| Chpt. 12 Accidents, Properties, Absolute Accidents | I.v, I.vii |

| Chpt. 13 Real, Essential, and Non-Essential Predication | I.v.1-3 |

| Chpt. 14 Syllogistic Truth |

| Part V. | Errors |

|---|---|

| Chpt. 15 Described and Refuted, 1 and 2 | |

| Chpt. 16 Described and Refuted, 3 through 11 |

| Part VI. | Further Issues |

|---|---|

| Chpt. 17 How a Necessary Truth is True | DAA II |

| Chpt. 18 Another Response | |

| Chpt. 19 Passio is a Subject | |

| Chpt. 20 Universals and Intelligences, Angels | |

| Chpt. 21 Counterfactual Universals |

[1] Transubstantiation is the Roman Catholic belief that the consecrated bread and wine of the sacrament of Eucharist take on the substantial being of Jesus Christ, despite appearing to remain bread and wine. It was developed in the thirteenth century, and remains an important Catholic teaching. Return

[2] See Marcela Perett, `A Neglected Eucharistic Controversy` Church History March 2015 for an overview of the post Wyclif Bohemian Eucharistic controversy. Return

[3] Et multi minus videntes haeriticant eum in hoc facto et in aliis et maculant famam eorum, qui scripta sua legunt, non advertentes, quod inter spinas pulcherrimae rosae colliguntur…¨ quoted from Ioannis Hus et Hieronymi Prag. Historia et monumenta Norimbergae 1558 p.267, in Jan Sedlák, ¨Eucharisticke traktaty Stanislav ze Znojma¨Hlidka 1906 vol.23 no.1 pp.6-12, n.8. Return

Bibliography

- Vilém Herold, Pražská Univerzita a Wyclif Prague 1985

- Howard Kaminsky, A History of the Hussite Revolution, University of California 1967, J. Kratochvil, ¨Problem všeoběcin v české filosofi xiv stoleti¨ Studie a texty k naboženským dějynam českým IV 1925

- K. Laburda, `Master Stanislaus of Znojmo His Life and Works` Ph.D. dissertation unpublished, 1950

- Stephen Lahey, ¨Stanislaus of Znojmo and Prague Realism: First Principles of Theological Reasoning¨Kosmas, 2, 2015, pp.9-26

- Stephen Lahey ¨Stanislaus of Znojmo and the Ecclesiological Implications of Wyclif`s Doctrine of Divine Ideas¨, Before and After Wyclif Stefano Simonetta, Luigi Campi, eds, forthcoming 2020

- Gabriel Nuchelmans, ¨Stanislaus Znaim on Truth and Falsity¨Medieval Semantics and Metaphysics Aristarium Supplementa II 1985, pp.313-338

- Jan Sedlák, ¨Filosofické spory pražske v době Husově¨, Studie a texty k naboženským českým II, Olomouc, 1915, pp.197-262

- Jan Sedlák, ¨Stanislav ze Znojma v Moravě¨ Hlidka 24

- František Šmahel, ¨Circa universalia sunt dubitationes non pauca I-III¨Filozofický časopis 18, 1970, 987-997

- František Šmahel, Üniversalia Realia sunt Heresis Seminaria¨, Československý časopis hisotorický XVI, 6, 797-811

- František Šmahel, ¨Verzeichnis der Quellen zum Prager Universalienstreit 1348-1500¨Mediaevalia Philosophica Polonorum, 25, 1980

- František Šmahel, ¨Wyclif`s fortune in Hussite Bohemia¨Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, 43, 1970, pp 16-34

- Stanislav Sousedik, ¨Pojem `distinctio formalis` v českých realistu v době Husove¨Filosofický časopis 18, 1970, pp.1024-29.

- Stanislav Sousedik, `Stanislaus von Znaim (d.1414) Ein Lebenskizze` Mediaevalia Philosophica Polonorum 17, 1973 pp.37-56

- Evžen Stein, ¨Wiclif a tzv.vystředni český realismus¨Česky Časopis Historicky 47, 1946, pp.55-74

- S.H.Thomson, ¨Some Latin Works Erroneously Ascribed to Wyclif¨, Speculum 3 1928 382-391