by Walid SALEH

I was not going to the USA to study Qur’an commentary tradition. That was not the plan. I came to graduate school to study the Qur’an, in the manner of Biblical Studies (higher criticism). There I was reading up on scholarship on the Qur’an. I read a book on folklore and the Qur’an, and in it the author mentions that one of the most important Qur’an commentaries in Islamic history is still unedited!!!!!!! I said WHAT!!!!! This was 1994. A moment that would define my academic career, a side remark by an author.

Now, some background. I came to Islamic Studies from Arabic Studies, where editing the medieval Heritage of the Arabs was the name of the game, and one thought all the great works have been edited. In retrospect, I realised that Arabic Studies did not care enough about Islamic texts, and thus there remain hundreds of thousands of works unedited or unstudied. I said to myself, this is my chance to do something new. This was before the internet, before digitising, before collections believed in OPEN access policy. You have to grovel, travel and pay to get things! Oh man, you have no idea how difficult it was to get a copy of a manuscript. You certainly could not google. But mainly it was an expensive thing to do—to study manuscripts. Undeterred, I decided that this author Tha`labi (d. 427/1035) and his massive Qur’an commentary (Kashf) were going to be the topic of my dissertation. There were some problems (I am being euphemistic), this was a multivolume work, sprawling (I will later called it encyclopedic, the new critical edition is in 33 volumes, the uncritical in 10 volumes), meaning you just don’t get one manuscript and you have the work, you have to reconstruct the work; no collection has a full copy of the work. This meant ordering as many individual volumes as you can to reconstruct a running complete copy (so a collection will have volume one, another the last volume, and each was of different length, so a complete set was between 10 volumes to 4 massive volumes). The other major problem was disciplinary: The field of Qur’an commentary studies then was marginal at best and very low in the pecking order of things in Islamic Studies. Its main concern was early works and their authenticity, a loop of a few texts that forgot 1200 years of later development. My Tha`labi—is that too possessive?—was from the documentary period, when there was no doubt who wrote what and what was written. Authenticity—or the neverending search for it—was not there to make my work cutting edge. It was a gamble, and I knew it. I soon dropped the Qur’an (for the time being) and picked up Qur’an commentary. This is a massive genre of literature, copious and voluminous. It is here that the story becomes interesting. With no studies in Islamic Studies on classical Qur’an commentary to guide me, I turned to Jewish studies, which then was in the midst of the Middrash turn revolution. Everybody was doing Middrash, and I read voraciously.

If there is a continuity in my work, it is that this SSHRC project is a globalization of that moment of discovering another discipline. To know about other fields is not a charity, it changes how we do our work, for the better.

But there I was, determined to make a statement on a field stuck with few texts, and to make a point to my PhD adviser that there was no way I would not study this work (he said it was too big for me). On a Thursday, the day of his weekly seminar, I took the train (I had not left New Haven since I arrived from Lebanon then), and headed to Princeton, New Jersey to their library. I forgot to say that I discovered four volumes of the work in North America! This was cheaper than ordering microfilms, those ugly dark inked things, ruinous to the eyes, no colour, no depth.

It was at Princeton that I discovered Garrett 2217Y (Princeton has the most important collection of Arabic mss in North America). This was a prachtig (a fabulous manuscript, prachtig is German for fabulous). Just beautiful, you see Qur’an commentaries are not given this treatment. It has the original binding, it has a colophon and a date! What more does one want. I would eventually find other copies (one from Madina in Saudi Arabia), but no copy in the world matched the care and expensiveness of this Princeton copy. I knew I would come back to it one day.

Twenty-six years later, just before Covid19, I got in touch with Princeton collection and asked for a digital copy, not a microfilm copy, which I own. I wanted one that can zoom, show the colour, and just enjoy. Now, the fee was a miserly 39 dollars (or is it 19—I forgot). You click on a link, you pay by credit card, you move not! They got back to me, they said it is not one that is digitised, they have to check with the curator to determine if it is in a state of preservation to allow it! I knelt and prayed. The computer said YES. Covid19 came, a silence fell. I hear not from them.

Two days ago, an email with a length apology arrives—is there any one nicer than librarians? seriously!—with a link and a click. I was confused. You see, they not only digitised it for me, but for the whole world to see. And wow: you have a high resolution option, and four other options that—I don’t know what!—each of different resolution.

Now here is the link so you can see what I mean.

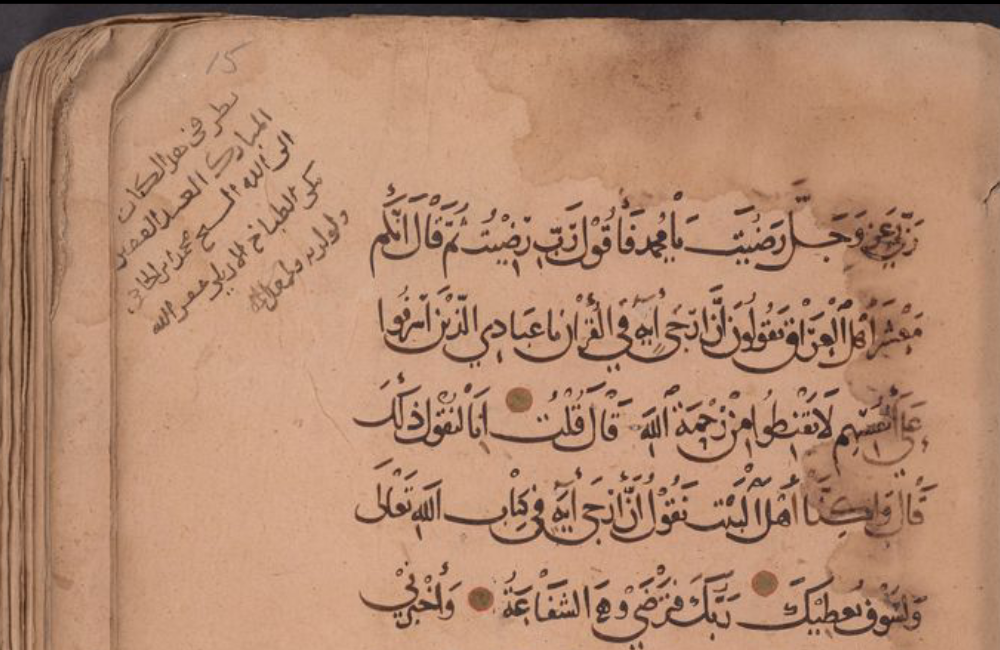

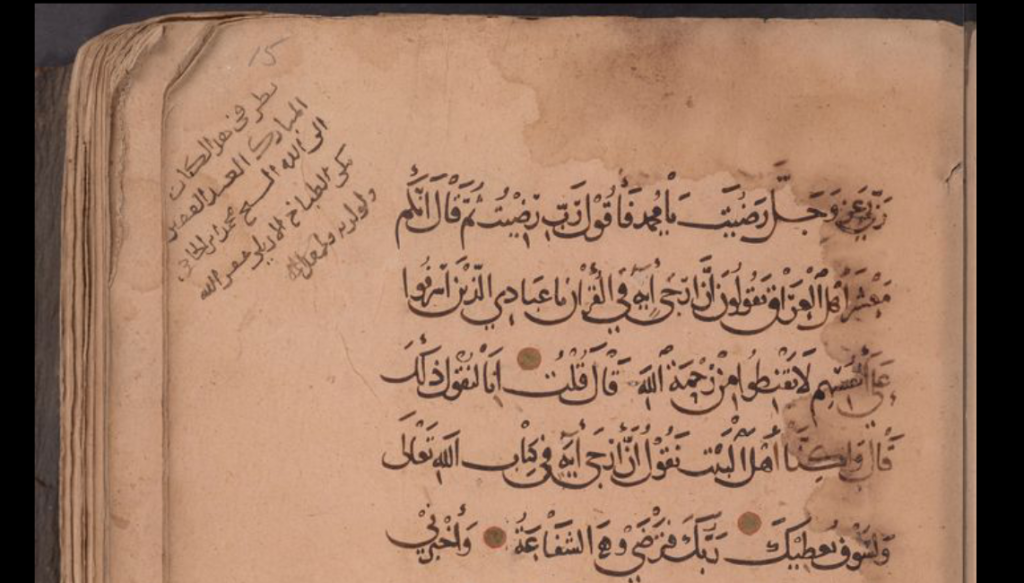

Princeton Arabic mss Garrett no. 2271Y, f.15a detail with marginal comment.

What it is about Garrett 2217Y that makes it unique:

First, it is the last volume of the work, which means the lost set it was part of was most probably written—i.e. it must have belonged to a set of mss that resembled it in style, paper, etc. Second, it is dated: the colophon states that it was written in 600 of the Hijra (Feb. 5, 1204 to be exact). We have the name of the scribe and his provenance (Baghdad), this was before the Mongol invasion by 50 years or so. It is also one of the earliest copies of the work we have.

Third: this is an expensive manuscript, with only 11 lines per page (10 words per line). This is an overkill—Qur’ans are usually treated this way, or very very fancy copies of short works. Not a massive Qur’an commentary. This is also executed by a professional scribe, a masterpiece of penmanship. Fourth: I have calculated that if this belonged to a set that used the same style and dimensions, then the set would be in 26 volumes. This would make it one of the largest sets of this commentary to survive. Fifth: this copy has been authenticated, that is, the scribe tells us every 10 folios that he checked the copy. He has an editorial note on the margin: it has been proofread against the vorlage (the original). It is not clear if he means a copy by the author? Or the vorlage. In either case, this is very close to the age of the author, just 175 years since Tha`labi died; the vorlage must be very close to the age of the author, if not a copy of his.

These are preliminary remarks on the value and significance of this manuscript. Now with the recently published critical edition of the work, I can also make extensive comparisons between this copy and the other copies.

The reason I came back to Garrett 2217Y is that it can be used as a reference point, both as dated paleographic evidence, and as a way to measure the significance of works and how they are copied. It deserves its own introduction, and its own place. It upends our expectations of how works were copied—if you look at later copies of the work, you will see that multivolume works were condensed for economic reasons. This work will settle eventually on being a 4-volume work from the 16th century onward in Istanbul.

We are at an interesting moment in our relationship with collections: we can influence them. If I had not written to them, they would not have digitized it. Each one of us can influence their field this way now, establish contacts with curators, and make our field more accessible.

Background image: British Library. Egerton MS 872, fol. 199r. Pentateuch with the Hafṭarot, Five Scrolls, and Rashi’s commentary, 1341.Source: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Egerton_MS_872