Featured image: P3861, item 9; folios 62–63. Sanskrit prayer tranliterated in Tibetan script with interlinear Chinese notations and additions. Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

by Amanda GOODMAN

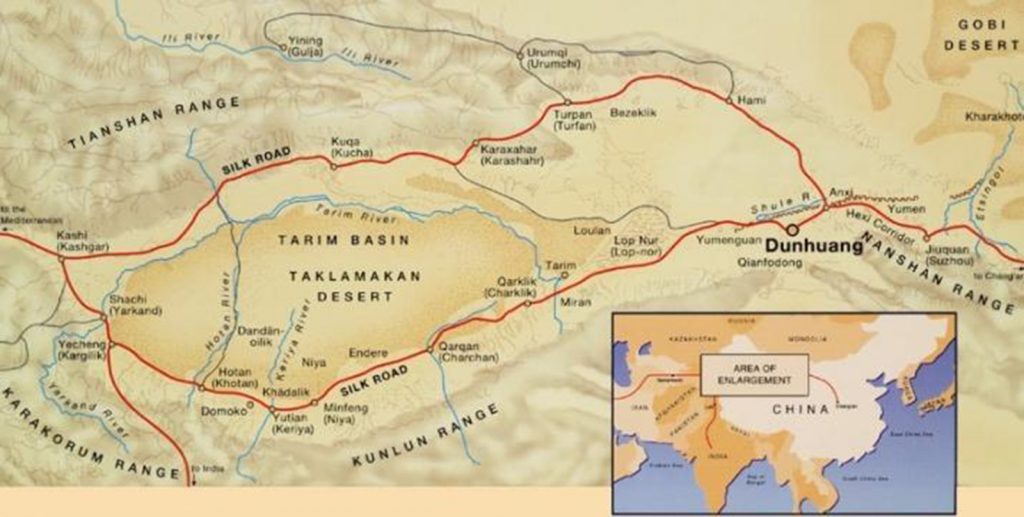

Over the past decade, I have spent a lot of time thinking about the Buddhist communities that flourished in the region of the Dunhuang Buddhist cave site in present-day Gansu province, China. Situated along the old Silk Road (fig. 1), Dunhuang served as a military garrison, way station, and pilgrimage site for well over a thousand years in what was then—and to a certain extent remains—a nexus of a wider regional “crossroads” populated by significant Chinese, Uyghur, and Tibetan communities. Many of these were Buddhist communities that left their traces in the books, buildings, and byways that for centuries lay buried beneath the desert sands.

At the turn of the twentieth century, a series of imperially-backed expeditions led to the “discovery” of tens of thousands of manuscripts in a side chamber—commonly referred to as the “library cave”—of one of the nearly 500 excavated rock-cut Buddhist cave shrines that comprise the Dunhuang cave complex (fig. 2). The Dunhuang manuscript “archive” was thus born out of these colonial projects, one result being that the excavated manuscripts, together with significant numbers of sculptures, portable paintings, ritual paraphernalia, and even some wall murals, were scattered across dozens of international institutions, forming a kind of global Dunhuang network.

(See Sam van Schaik’s Early Tibet Blog, Secrets of the Cave II: The “Library Cave”)

One positive outcome of this dispersed “network” has been a large-scale digitization project initiated by the International Dunhuang Project at the British Library and partner institutions. This project aimed at creating an open-source database of Dunhuang documents available for public use—a database to which all scholars of Chinese and Tibetan literature, history, and religion, myself included, are deeply indebted.

Although the Dunhuang collection contains upwards of 50,000 individual manuscripts spanning some seven centuries, the bulk of the Dunhuang documents date to the 9th and 10th centuries. This includes a large number of Chinese and Tibetan ritual manuscripts that circulated in the second half of the 10th century specifically. The bulk of these manuscripts contain study and practice materials (primers and sourcebooks, vidhis, breviaries, and so on) that circulated in unique book formats (pothi and concertina booklets, etc.) outside the official canons; this material reflects multiple stages in the development of Buddhist ritual, or competing ritual systems, sometimes on a single manuscript. These manuscripts help us to reconstruct local Buddhist life in the region.

The alternation of languages across the individual items inscribed side-by-side helps identify this manuscript as part of a constellation of related manuscripts with similar form and content, all of which appear to have circulated in the final decades of the 10th century.

One particularly compelling piece of manuscript evidence for reconstructing local Buddhist training and practice communities comes in the form of a small stitched booklet now housed in the Pelliot chinois collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. no. P3861 (fig. 3). The manuscript is remarkable in many respects, not the least of which is the fact that it contains a combination of Buddhist expository and ritual writing in three languages: Khotanese, Chinese, and Tibetan (it actually includes a fourth language, Sanskrit, but we’ll get to that below). The alternation of languages across the individual items inscribed side-by-side helps identify this manuscript as part of a constellation of related manuscripts with similar form and content, all of which appear to have circulated in the final decades of the 10th century. This is important because it means that these manuscripts were circulating just prior to the sealing of the library cave.

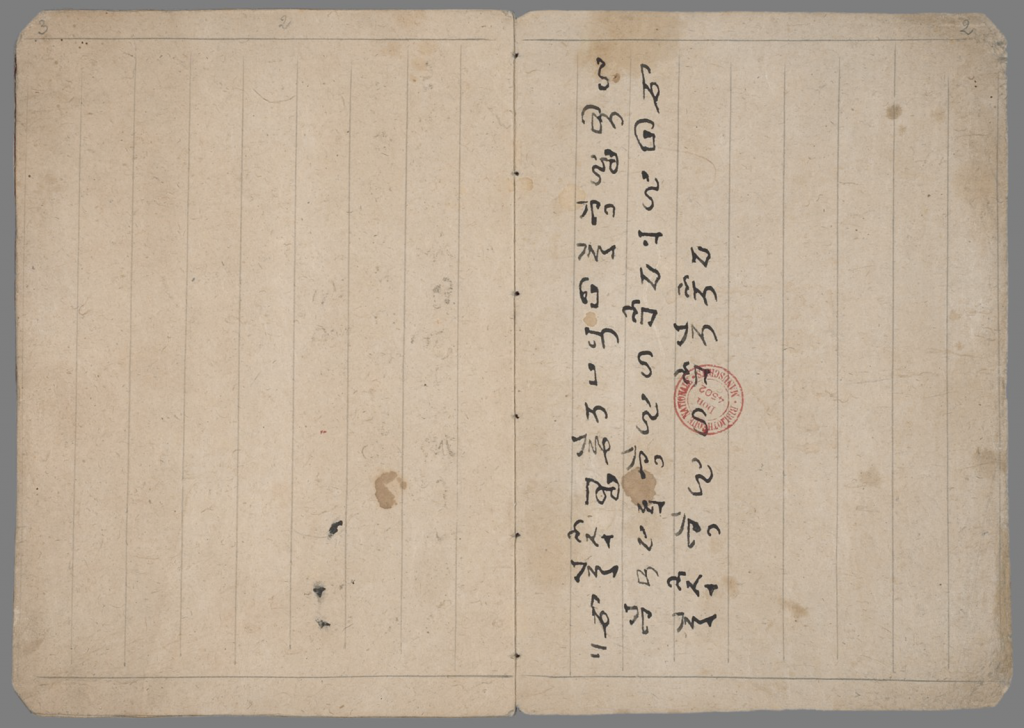

Like many Dunhuang Buddhist documents, P3861 contains a short dedicatory inscription, this one (fig. 4.) written in Khotanese. (Khotanese is an Eastern Iranian language that was used in the southern Silk Road kingdom of Khotan, which had close ties to the ruling house of Dunhuang during the 10th century in particular.) The inscription contains what appears to be the name of the owner of the booklet, or at least the name of the person who commissioned its production and the copying of its texts. We have many fine examples of dated colophons that contain the names of local figures who are, in turn, traceable across documents preserved at the site.

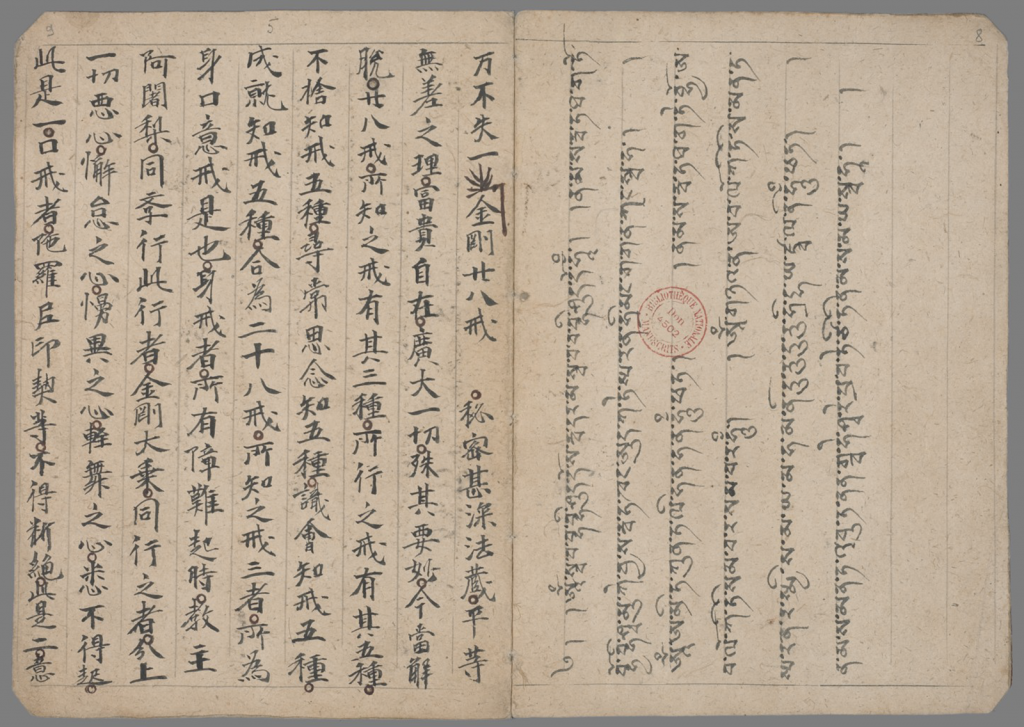

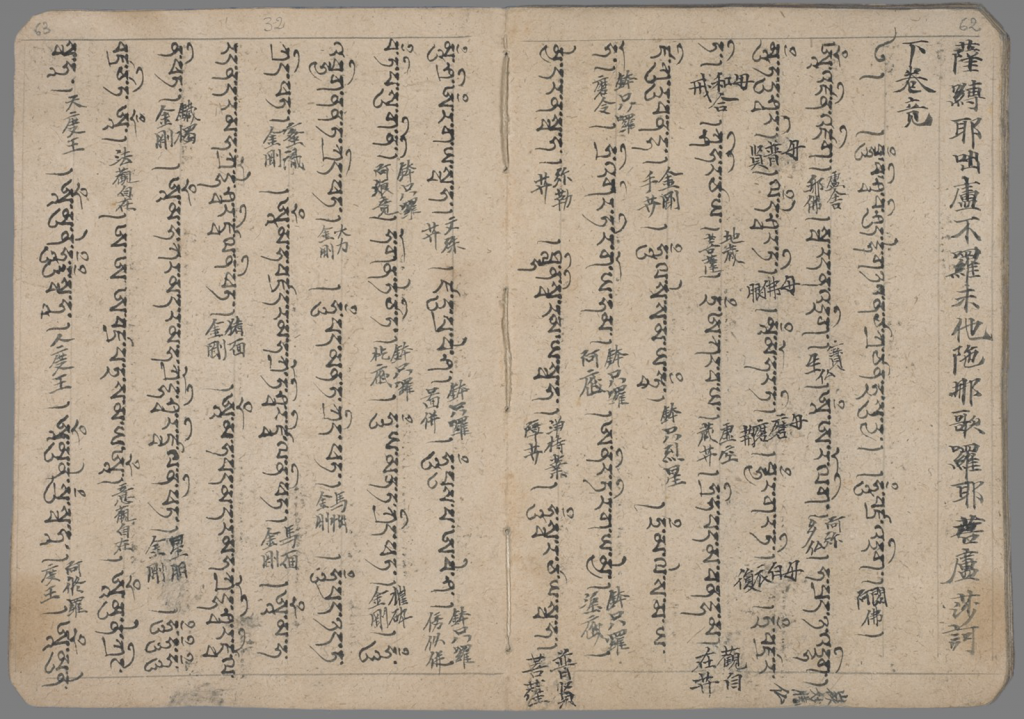

Several features indicate that our booklet was manufactured locally (fig. 5): the booklet was made using local paper; it appears to have been written using a pen (a relatively common writing device at the site during this period); it contains alternating text in multiple languages (and represented using different scripts); it contains distinctive highlighter and punctuation marks found on other materials from the site; and its maker used a modular method to compile its disparate texts. One of dozens of composite manuscripts from Dunhuang, P3861 is representative of the types of compilations people were making and likely using at Dunhuang.

Scholars speculate that the booklet once served as a sourcebook, or primer, prepared for, or perhaps by, local adepts seeking entry into the Buddhist tradition. Not only does it contain an assortment of common Buddhist prayers, including dhāraṇī extracts (that is, Buddhist spells or mantras) that one might expect to be required learning for someone undertaking ritual training or practice. In addition, it contains a short treatise on the tantric precepts or samaya vows to be observed by Buddhist practitioners, as well as an introductory-level text explaining basic Buddhist concepts that we know was used in later Chan Buddhist study circles (a medieval “Buddhism 101” textbook, if you will). An outline of the complete contents of the manuscript is presented here:

| Item | Language |

|---|---|

| 1. Short inscription on the aspiration to awakening | Khotanese, Brahmi script |

| 2. Preliminary purification rite, including a gtorma offering to the deity Avalokiteśvara | Sanskrit formulary written in Tibetan script |

| 3. Expository text on the tantric samaya or precepts | Chinese |

| 4. Food distribution text (rite for the Buddhist dead) | Chinese |

| 5. Five-buddha contemplation text | Chinese |

| 6. Unidentified contemplation text | Chinese |

| 7. Discursive text on the “Three Categories of the Teachings” | Chinese |

| 8. A dhāraṇī (spell) miscellany | Chinese |

| 9. Prayers, including the Vajrasattva mantra | Sanskrit syllables transliterated in Tibetan script, with additional text in Chinese |

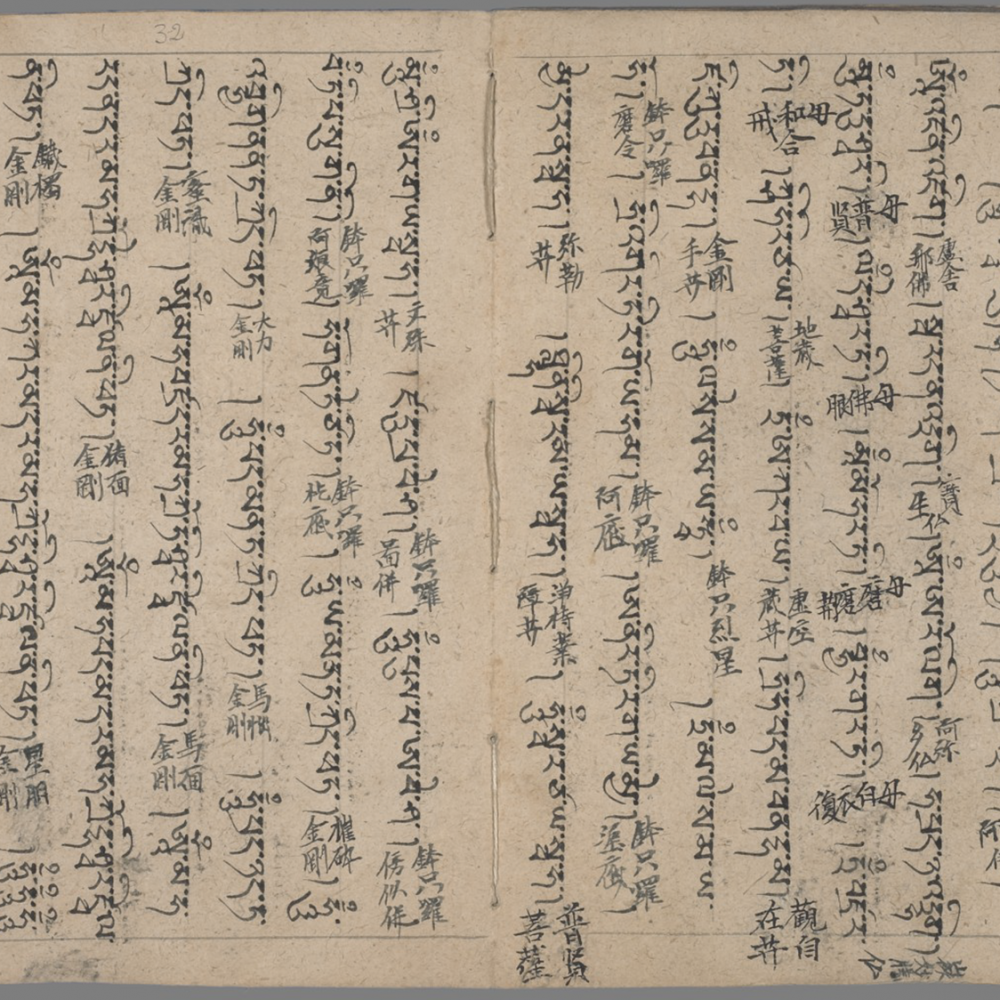

Perhaps the most visually striking item on the manuscript is its last, which contains prayers composed in Sanskrit but transliterated in Tibetan uchen (dbu can) script (fig. 6). A series of neatly placed Chinese notations appear to have been added between the lines of Tibetan. The Tibetan text, which is arranged vertically from top to bottom, left to right, stands in contrast to the inserted Chinese glosses which are arranged horizontally and read from top from bottom, right to left. A careful reader of the text would have been forced to manually turn the booklet to take in both sets of information.

Curiously, the Chinese glosses are not translations of the nearby text (which, again, is Sanskrit transliterated in Tibetan uchen script); instead, they provide, among other things, the names of deities comprising what I guess to be a Buddhist maṇḍala configuration (a Buddhist maṇḍala, in its simplest form, is an assembly of powerful deities who congregate, when called upon, for the purpose of a specific Buddhist rite). Here, one might imagine a third, invisible layer of mediating text or traditional learning assumed by the scribe or copyist on behalf of their reader (again, possibly a novitiate monk, a seasoned ritualist, or a lay scholar) that would identify these prayers and deities with a specific ritual system or Buddhist text that we can only guess at today.

What we have are not translations of content from one language to another, but texts, annotations, and additions in different languages representing different types of information placed in close proximity on the page: expository writing next to ritual notetaking next to interlinear glossing.

As a whole, P3861 raises a number of fascinating questions about the types of study and practice materials that were being produced, and possibly used, by local Buddhist practitioners at Dunhuang during the late 10th century. Based on the manuscript evidence, many of these practitioners appear to have had facility in multiple languages. In fact, P3861 raises provocative questions about the usefulness of categories like “bilingual” or “multilingual” to adequately describe the manuscript. What we have are not translations of content from one language to another, but texts, annotations, and additions in different languages representing different types of information placed in close proximity on the page: expository writing next to ritual notetaking next to interlinear glossing.

For more than two millennia, Buddhist communities have been defined by their commentarial practices. Buddhist communities at Dunhuang were no different. One of the most exciting prospects for the SSHRC Practices of Commentary project is the possibility of interpreting a manuscript like P3861 outside the confines of Dunhuang Studies and Buddhist Studies, placing it instead next to other medieval exemplars from other established workshops to think more intentionally about the methods and logics used across manuscript and commentarial traditions. I look forward to the process of decentering commentary studies with samples like the one described above—and I look forward to the ways in which sources produced far from the scriptoria of Dunhuang might challenge my own interpretation of Buddhist traditions at this site.

Background image: British Library. Egerton MS 872, fol. 199r. Pentateuch with the Hafṭarot, Five Scrolls, and Rashi’s commentary, 1341.Source: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Egerton_MS_872